St. Teresa, Gerard Manley Hopkins and Thanksgiving

By DAVID KING, Ph.D., commentary | Published November 23, 2021

I am an impatient man.

Among my many faults I possess a persistent need for immediate gratification. When I want something, I want it now, and when it’s not readily available, I get frustrated.

This is why I know that it takes about five days to thaw a large frozen turkey, if indeed you are lucky enough to acquire a bird in this era of outrageous inflation and supply chain shortages. I’m sure the turkeys are grateful; it takes me longer to feel thankful.

We celebrate a formal Thanksgiving in the United States once a year, but of course we should be offering thanks all the time. Those five days of thawing and the hours of roasting that follow aren’t unlike the week before a Sunday Mass, and when we gather then we are truly expressing gratitude, for Eucharist literally means “thanksgiving.”

A statue of St. Teresa of Avila stands in the sanctuary of the Serra Chapel at Mission San Juan Capistrano in San Juan Capistrano, Calif., CNS photo/Nancy Wiechec

In her spiritual masterwork The Interior Castle, written in 1577, St. Teresa of Avila reminds us of a fundamental truth: “All things are passing … God alone suffices.”

Using the castle as a metaphor for the soul at prayer, Teresa imagines the structure as having seven levels, or rooms. Her “interior castle” is like our sheltered-in-place quarantine during the pandemic; emerging from it—rising out of it—invites us into the fullness of all that God offers, all that God is.

Three-hundred years later, in 1877, the prototypical English modern poet, Catholic convert, and Jesuit priest Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote a similar, though shorter, meditation upon permanence in the midst of change. Hopkins’ poem “Pied Beauty,” one of his self-named “Curtal Sonnets,” is a brilliant 11-line consideration of “dappled things,” those organisms, objects and natural phenomena we so often take for granted because even though they are charged with mystery, they have a tendency to blend in and go unnoticed.

The poem is brief enough to quote here:

“Glory be to God for dappled things—

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings;

Landscape plotted and pierced—fold, fallow, and plough;

And all trades, their gear and tackle and trim.

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him.”

The poem is Hopkins’ unique take upon a traditional Italian Sonnet form, though shorter and with a different rhyme scheme. This sound, as Alexander Pope said, echoes the sense; that is, the way the poem resonates in the ear says something about its theme: unchanging permanence in the midst of transience.

The poem also utilizes Hopkins’ “Sprung Rhythm,” which sought to free poetry from a rote and restrictive closed form of meter. Hopkins believed that poetry should be without formal borders or restrictions, and where such constraints did exist (as in the sonnet) they should be adapted to the poet’s own needs.

St. Teresa was trying to do the same thing with prayer. Both Hopkins and Teresa admitted that they often lost their way, and yet their groping for a sincere and honest expression of language was the same. In “tongues” they sought to grow closer to God, and both perceived that the key to that closeness was thanksgiving. Rather than asking for what we want, Teresa knew that we should instead express gratitude for all we have already received.

Hopkins bookends the poem with two short expressions of praise: “Glory be” and “Praise him.” The objects of glorification and praise are all “dappled things,” mottled, speckled, multi-faceted. When I imagine anything dappled, or its multiple synonyms, I like thinking of a subtext beneath a text, a deeper reality behind a superficial image. The scales and skin of a dappled trout are not the trout itself, but an invitation to look deeper at the whole trout. We see the exterior; we should be invited by it to examine more closely the interior.

Consider other movements in modern painting such as Impressionism, Cubism, Abstract Expressionism—what we behold immediately is not necessarily the essence of the whole. Is this not like our attempts at prayer, such as Teresa described?

The mystery of transience and change

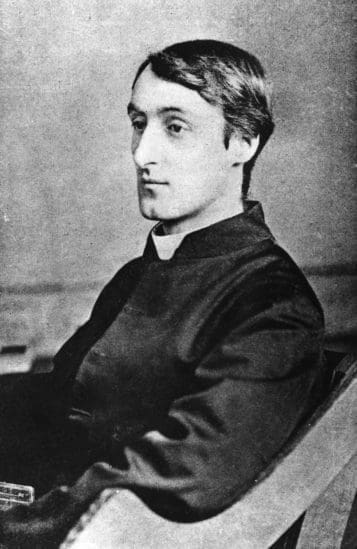

This is an image of Jesuit Father Gerard Manley Hopkins. Father Hopkins was an English poet of the Victorian era. CNS photo/courtesy the Jesuits in Britain

As a Catholic and a priest, Hopkins knows full well he is in the company of St. Paul’s spirituality, and he recognizes the connection to the Eucharist and what exists fully in the host. Like the simplicity of bread and wine used in the Eucharist that contain a profundity not immediately seen, Hopkins notes this same fullness in the lives of nature and humanity.

The poem is certainly autumnal; it’s perfect for the end of fall and the season of Thanksgiving. Mottled skies, trout and finch, farmland, and chestnuts are all images we associate with this time of year. Yet Hopkins isn’t setting a centerpiece for a table or tromping happily through falling leaves. As the second stanza of the poem makes clear, he’s looking at the mystery of transience and change, as well as a paradox.

The cow, the finch, the trout; the very sky and land; our own work—all these things are beautiful to behold, and yet all of them are constantly changing; like us, they’re “fickle.” As Robert Frost wrote in one of his own autumn poems, “nothing gold can stay.” The wonderful ninth line, where Hopkins balances “swift and slow, sweet and sour, adazzle and dim,” is a perfect image of all that we see in nature and ourselves, for good and bad.

Glory be. Praise him. How often do we use these phrases? The practicing Catholic uses them all the time, so much so that their meaning risks fading. “He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change.” In all the frenzy of the hurried world, Hopkins calls us to look at nature, and in looking at nature, we view ourselves, and in considering ourselves, we draw closer to God. And God alone is constant; unlike creation, which constantly changes, God constantly endures. I love the pun inherent in “past change,” where “past” means both time passed and beyond.

St. Teresa and Hopkins remind us that prayer is both deep within us and all around us, and whether we look inside or out, thanksgiving should inform our gaze. This is not easy. It wasn’t easy for Teresa, who experienced self-doubt, and it wasn’t easy for Hopkins, who suffered from episodes of depression. It’s certainly not easy for me, with my impatience and appetites. Hopkins once complained to his mentor and sponsor St. John Henry Newman about his state of mind, and Newman’s advice was simple: “Give alms.” In short, Newman said, consider others, and in thinking of others, give thanks.

In a time of upheaval, division, fear, and doubt, what lasts? What endures? Gratitude and glory, world without end. Thanksgiving isn’t just a day; it’s a process. May you and your family have a happy Thanksgiving, both today and throughout the days to come.

David A. King, Ph.D., is professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and director of RCIA at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.