The minister’s black veil

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D. | Published August 14, 2020

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, I have been continually flummoxed by the debate over the wearing of masks.

My puzzlement isn’t informed so much by outrage or disbelief, nor is it necessarily self-righteous or sanctimonious. I learned a long time ago that while most people will do the right thing, many people will not; not everyone understands the simple fundamental Catholic belief that because our actions always affect others, we should seek to act in the interest of the common good.

No, I’m most surprised at the mask furor because we live in a culture that usually seems to honor the wearing of masks.

Halloween—and its celebration of the disguise—has become our most popular secular holiday, far removed from its religious roots. Masquerades and costume balls conjure mystery and sophistication. Among our most cherished pop-culture myths are the mask-wearing superheroes—Spider-Man, Batman, and the myriad others from comic books and movies. Our most powerful social media platform is, of course, Facebook.

Even our most watched athletes, the football players in the colleges and the NFL, are hidden from view by helmets, face masks and plastic shields. Indeed, one of the most severe penalties in American football is levied for interference with another player’s face mask.

Our healthcare workers—our newly appointed heroes—are defined by their iconic masks.

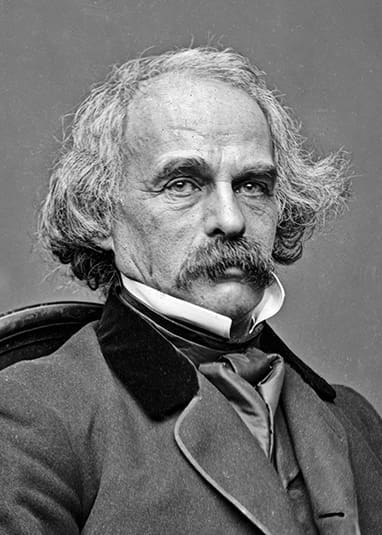

Nathaniel Hawthorne

And, admit it, at least once during this ordeal, someone probably said to you, “Who is that masked man (or woman),” referencing both your awkwardly arranged face covering and the Lone Ranger.

Not surprisingly, the mask is therefore prominent in our American literature. Given the current context of the national protests for racial justice, I’ve thought frequently of Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poem “We Wear the Mask.” The poem begins with the confession that “We wear the mask that grins and lies,/It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,” and concludes with the lament that “We smile, but, O great Christ, our cries to thee from tortured souls arise.”

I’ve also been thinking about Nathaniel Hawthorne, one of our greatest early American writers, who founded a uniquely American literature upon our “usable past” of the Native Americans and the early Puritan settlers, among them those who presided over the Salem Witch Trials.

At the heart of Hawthorne’s fiction is his great theme, the guilt of secret sin that we keep concealed in “that darkest of prisons, the human heart.” Hawthorne wrote that indeed “the fiend in his own shape is less hideous than when it rages in the breast of men.” In great novels, particularly “The Scarlet Letter,” and in allegorical short fiction, Hawthorne continually explored the universality of sin and guilt, both of which we attempt to conceal from others.

This theme is perhaps most apparent in Hawthorne’s story “The Minister’s Black Veil,” which was first published in 1832 and reprinted a few years later in Hawthorne’s famous collection “Twice-Told Tales.” Hawthorne subtitled the story “A Parable” and noted that he had been influenced by the case of a clergyman in Maine.

The story concerns The Reverend Mr. Hooper, a parish minister in a New England Puritan village. One Sunday morning, Reverend Hooper appears at the church with his face covered with a veil “Swathed about his forehead, and hanging down over his face, so low as to be shaken by his breath.” The parishioners are immediately aghast: “I don’t like it!” “He has changed himself into something awful!” “Our parson has gone mad!” They sound ready to go viral on a Twitter video.

Though the veiled Reverend Hooper’s first sermon from behind the mask concerns “secret sin, and those sad mysteries which we hide from our nearest and dearest, and would fain conceal from our own consciousness, even forgetting that the Omniscient can detect them,”as time goes by, “It was remarkable that of all the busybodies and impertinent people in the parish, not one ventured to put the plain question to Mr. Hooper, wherefore he did this thing.”

The people have entirely missed the point of what the parson wants to teach them. Mr. Hooper confides in his wife that he will never remove the veil, and he tells her as well that whether they know it or not, all his parishioners wear a veil, but that “There is an hour to come when all of us shall cast aside our veils.”

What unites us

Hawthorne’s stories are always marked by ambiguity. Parson Hooper wants to teach his parish the lesson that all of us are afflicted by the sins we keep secret from God and our fellows. He wants to demonstrate the danger of obsessing over what another conceals instead of addressing our own sins.

Yet paradoxically, the veil also teaches the minister a lesson: “Thus from beneath the black veil, there rolled a cloud into the sunshine, an ambiguity of sin or sorrow, which enveloped the poor minister, so that love or sympathy could never reach him.” Though the veil allows him to become “a very efficient clergyman . . . a man of awful power over souls that were in agony for sin,” it also causes the Reverend to become isolated and alone.

Upon his deathbed, Hooper’s wife prepares to remove the veil that “All through life had hung between him and the world: it had separated him from cheerful brotherhood and woman’s love, and kept him in that saddest of all prisons, his own heart: and still it lay upon his face, as if to deepen the gloom of his darksome chamber, and shade him from the sunshine of eternity.” The parson attending Hooper’s death implores him to allow the removal of the veil, but Hooper won’t allow it.

Then, as Hawthorne so often does, he clearly states one moral of his parable: “Why do you tremble at me alone? Tremble also at each other! Have men avoided me, and women shown no pity, and children screamed and fled, only for my black veil? What, but the mystery which it obscurely typifies, has made this piece of crepe so awful? When the friend shows his inmost heart to his friend; the lover to his best beloved; when man does not vainly shrink from the eye of his Creator, loathsomely treasuring up the secret of his sin; then deem me a monster for the symbol beneath which I have lived, and die! I look around me, and, lo! On every visage a Black Veil!”

Hawthorne was not a Catholic; he was attracted to American Transcendentalism more than a formal church, and he did not live to see his daughter Rose convert to Catholicism. Rose went on to found the Dominican Nuns of Hawthorne, who to this day operate the Our Lady of Perpetual Help Cancer Home in Atlanta. The nuns were well known to one of Hawthorne’s greatest progenies, Flannery O’Connor; they even convinced O’Connor to write an introduction to their “A Memoir of Mary Anne,” and the essay acknowledges the debt O’Connor owed to Hawthorne’s writing and worldview.

But Hawthorne certainly knew a great deal about sin, redemption, and universal human nature and experience. He even implicates the reader in the story, and it is an uncomfortable implication. What is Reverend Hooper hiding? What did he do? So, we imagine, and we make conjectures, and we gossip, and we lose sight of our own transgressions. No wonder Alfred Hitchcock, like his contemporary O’Connor, became a great allegorist in the Hawthorne tradition.

We are a fallen people, and certainly we all have sinned. Yet in times like these, we should focus perhaps not so much upon what divides us but unites us. Rather than condemning, we can try to empathize. Like Reverend Hooper, we can let our actions speak for us, so that when we “mask up” for the store, or the office, or the Mass we can remember what the Parson teaches us with his veil: yes, truly, we are all in this together.

David A. King, Ph.D., is professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and director of RCIA at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.