‘A Taste of Honey’ depicts sweetness of enduring gift of love

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published October 19, 2017

One of the great blessings of my life has been the ability to be a hands-on father for my two boys. From the time my sons were born, I had the gift of sharing with my wife almost all aspects of caring for our children. They were happy days, and sadly not typical for most men.

You don’t really see the fundamental goodness in your fellow human beings until you venture out in public with a stroller and all the other accoutrements necessary for the care of small children. I still remember how people held doors for me, offered to assist with packages and groceries, and complimented me on my handsome babies. There is no smile quite like the smile directed toward a man out with his children.

You don’t really see the fundamental goodness in your fellow human beings until you venture out in public with a stroller and all the other accoutrements necessary for the care of small children. I still remember how people held doors for me, offered to assist with packages and groceries, and complimented me on my handsome babies. There is no smile quite like the smile directed toward a man out with his children.

Yet I also remember my shock at the most common words expressed to me by strangers during those days, “Babysitting today, huh?”

No. You see; it’s actually called parenting, and yes, men can do it quite well, thank you!

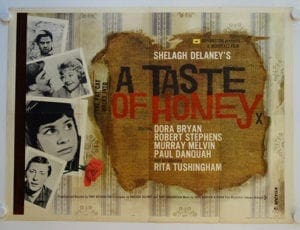

I thought of that attitude, which is far too common in our society, just a few days ago when I screened the marvelous adaptation of Shelagh Delaney’s play, “A Taste of Honey.” The film features an incredible portrayal of cultural stereotypes, including attitudes about men and childrearing, that are particularly striking considering that the movie appeared in 1961.

Delaney was born in 1938 to an Irish Catholic working class family in Salford, a district in metropolitan Manchester, England. Though she often struggled in school, she showed a talent for writing, and at the age of only 18, her first play, “A Taste of Honey,” premiered on both the London and Broadway stages. Though she went on to write other works, she will always be remembered for “A Taste of Honey,” especially for the screenplay she wrote for the film version, directed by Tony Richardson.

“A Taste of Honey” is often included among the many films, novels and plays that comprise a renaissance in British theatre and cinema. Usually referred to as “Kitchen Sink Realism” or “The Angry Young Men,” the movement developed in the late 1950s as a reaction from educated British working- and middle-class writers weary of the economic and cultural limitations imposed upon them by postwar society. Key writers and filmmakers of the period include John Osborne, David Storey, Alan Sillitoe, Karel Reisz, Tony Richardson and Lindsay Anderson. Important texts from the movement include “Look Back in Anger,” “This Sporting Life,” “Saturday Night and Sunday Morning” and “The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner.”

“A Taste of Honey” is similar in style to many of those works, all of which were also adapted as films, yet its tone is one of resignation rather than revolution, and it is deeply infused with love. Even in its dreary, rugged setting, the film has a gentle sweetness and a uniquely Northern England sense of humor.

Not that there is really anything to laugh about.

“A Taste of Honey” centers upon a 17-year-old girl, nicknamed Jo, brilliantly played by Rita Tushingham. Jo lives in Salford with her cruel mother, Helen, also marvelously acted by Dora Bryan. Living is not really the right word; Jo and Helen subsist. They move from flat to flat, often skipping rent because Helen can’t afford it. What little money they do have Helen spends in pubs where she drinks too much and falls under the sway of malicious men. Jo’s only ambition is to get out of school, which she hates, and find a job so that she can make her own way in the world, away from the influence of Helen and her alcoholic suitor, Peter. One weekend, Jo goes with Helen and Peter for a holiday in Blackpool, but Peter cruelly sends the girl home alone. Arriving back in Salford, Jo spends her time with Jimmy, a young black cook who works on a ship currently docked in Manchester. After Jimmy helps Jo bandage her knee following a nasty fall she takes at school, they immediately fall in love; they become, literally all the other really has.

The relationship between Jimmy and Jo is beautifully, even sweetly filmed; it remains one of the most touching screen romances I’ve ever seen. Inevitably, however, Jimmy has to return to sea. Our last look at him is in an enduring long shot, as Jo watches Jimmy peeling potatoes on deck while his ship recedes further into the distance. Jo knows, and we know, that she will never see him again.

Eventually, Helen and Peter marry, and Jo is left alone. She takes a job in a shoe store and rents a ramshackle flat in a crumbling block of Protestant council houses. One afternoon, as she prepares to close the shoe store, a rather effeminate young man comes in for a pair of Italian casual shoes, and Jo makes her first sale. A few days later, Jo meets the boy, Geoffrey, at a Catholic procession in town, and Geoff invites her to attend the fair with him. It becomes apparent that Geoff is gay, but Jo doesn’t mind, and the two quickly become friends. It also becomes apparent that Geoff is homeless, so Jo invites him to stay with her. Geoff does stay, and quickly makes himself busy decorating the flat and becoming what Jo calls her “big sister.”

Similar to the relationship with Jimmy, the friendship between Jo and Geoff is beautifully portrayed. The Mancunian humor is wonderful; the banter between them sharp and believable. The empathy each has for the other’s situation touching, yet never sentimental. Though neither is really either happy or sad, they face each passing mundane day with a bemused resignation that though they are effectively alone in the world, they at least have each other.

We sense, even before Jo and Geoff do, that Jo is pregnant. When Jo confides to Geoff that she is going to have a baby, he simply says that he’s not surprised. Jo tells Geoff the story of Jimmy, and tells him that her baby will be black. Again, Geoff is neither shocked nor judgmental. Indeed, in the best part of the film, Geoff is adamant that he will be the baby’s father. Despite his homosexuality, he offers to marry Jo so that the unborn child will have a family. In one memorable scene, Geoff even goes to a National Health pediatrician to get materials about how to be a good mother.

Consider again that this film appeared in 1961, and marvel at how topical its subject matter is for our own time. Then consider how matter-of-factly the complex and controversial issues of interracial relationships, homosexuality, substance abuse, homelessness and unwed mothers are presented without sanctimony or self-righteousness. The portrait of these multiple themes can’t even really be considered frank; people and situations are simply what they are.

Jo doesn’t care that Jimmy is black; she only knows that she loves him. Jo doesn’t question Geoff’s sexuality or his poverty; she only knows that he is a good human being. Jo tolerates her mother’s abuse because she empathizes with Helen’s essential loneliness. And not for a moment does Jo even consider terminating her pregnancy. Though she is afraid, and though she often honestly acknowledges that she does not want to have the baby, as a child herself born out of wedlock, there is simply no way that she will not have her child. The thought of abortion strikes her simply as “terrible.” She won’t even consider it.

Though Delaney appears not to have practiced her Catholicism, “A Taste of Honey” makes it obvious that she understood some of the fundamental tenets of the faith. Jo keeps the greatest commandment to love one another, and she keeps it just as Jesus demonstrated with Zacchaeus, Mary Magdalene, the woman at the well and countless others. She makes no judgments; she simply loves.

In many ways, the film is like a modern rendering of the parable of the Good Samaritan. Jimmy and Geoff help Jo when she needs it, and Jo helps them. It does not matter that they are all different, for they all know, as Geoff says, “you need somebody to love you while you are looking for somebody to love.”

Jo and Jimmy and Geoff live in a fallen world. They are surrounded by meanness. Helen and Peter are insensitive and racist. Jo’s block of flats is inhabited by cruel and mocking children. The river and the city streets are full of rubbish. The film even features a Guy Fawkes bonfire, an enduring example not only of nationalism, but also a subversive religious bigotry.

At a time when the Catholic Church is urging us to sustain the family, the domestic church, “A Taste of Honey” affirms the family’s dignity. At a time when our society is divided in multiple ways, films such as “A Taste of Honey” remind us of the enduring gift of love. We often speak of love’s power, yet “A Taste of Honey” reveals a deeper truth, love’s essential fragility. Jesus—destined to be broken himself—sought out the broken, the lonely, the sinful and the sad. “A Taste of Honey” reminds us of our own duty to love one another, no matter who they might be, and it remains a beautiful and relevant film.

David A. King, Ph.D., is associate professor of English and Film Studies at Kennesaw State University and director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church in Atlanta.