‘Brothers at Bat’ tells beautiful story of baseball and family

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published September 23, 2016

If you need to see me anytime this fall, you can make an appointment at either Holy Spirit Catholic Church or Kennesaw State University.

But I’m keeping office hours in a new location this autumn, and your best bet might be to find me in one of the dugouts at a local Little League ballpark. I’m there three nights a week, and Saturdays too.

My two boys have gone baseball crazy, you see, and this year we’ve even decided to give football a rest. We’re playing what the Little Leaguers call “fall ball,” and we are all loving it.

Of course, we’re also about to go insane, as we are juggling two different teams, two different practices, and several different games each week. It’s difficult to manage the activities of two young boys.

Imagine the challenge of having to keep up with 12 sons!

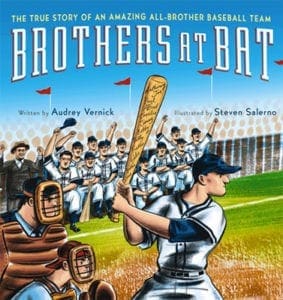

Regular readers of my column in the Georgia Bulletin know that at least once a year, I try to make space for a piece on children’s literature. These same readers know that I also frequently write about the connections between sports and Catholicism. In a great moment of serendipity recently, my older son came home from school with a book that immediately captured my attention and my imagination. The book is “Brothers at Bat,” by Audrey Vernick and illustrated by Steven Salerno, and it tells the true story of the 12 Acerra brothers of New Jersey, who played on the longest running all-brother team in baseball history.

Go play with your baseball cards, I told my son. I’m keeping the book.

You need to keep reading. You won’t find much information about the Acerra brothers in the Catholic press, other than a few glowing reviews of “Brothers at Bat” on Natural Family Planning websites. You won’t even find a Wikipedia entry on the brothers. Like me, unless you’ve been to the Baseball Hall of Fame (the Acerra Brothers, if not online, are at least enshrined at Cooperstown), you have probably never even heard of the Acerras, whose story is an amazing tale not only of baseball, but of dedication to family, faith and country. The story of the Acerra family is one that needs to be known, and “Brothers at Bat” does a splendid job of spreading the word.

Italian immigrant Luciano Acerra and American-born Elizabeth Lista were the parents not only of the 12 baseball playing brothers; in all, they had 17 children, 15 of whom lived into adulthood. One child died at birth, and another died in the Spanish Influenza pandemic, but the others lived long and productive lives after leaving the family home on Laurel Avenue in Long Branch, New Jersey. The last of the Acerra children to die was Frances Christopher Acerra, who though a girl, was appropriately nicknamed “Babe.” Frances died last year, just weeks shy of her 102nd birthday. Her brother, Edward, died two years ago at age 87. Edward was the last surviving member of the Acerra baseball team.

The Acerra brothers—Anthony, Joe, Paul, Alfred, Charlie, Jimmy, Bobby, Billy, Freddie, Eddie, Bubbie and Louie—all played at one time or another on the team that constitutes the longest playing team of its kind in baseball. The Baseball Hall of Fame registers 29 such teams in the history of the game; roughly 16 of them were competing during the era in which the Acerra brothers played. From 1938 to 1952, the Acerra team competed in Northeastern semi-pro leagues. Their father coached the team throughout its history and never missed a game.

The Acerra brothers, like most semi-pro teams all across America at the time, didn’t play in the green cathedrals we imagine when we think of ballparks. As the book describes, “The infields they played on were dirt; outfields were littered with rocks and sand. The brothers loved to talk about the day they played at the ‘old dog track,’ an oceanfront stadium that had once been an auto raceway. It was there that Anthony, the oldest, hit a couple of home runs right into the Atlantic Ocean.”

This sort of colorful and informative detail is one thing that makes the book so appealing, and in short descriptive paragraphs, we learn more about the brothers and the way they played the game. Anthony was nicknamed “Poser” because of his stance at the plate; Charlie was terribly slow, and Jimmy had an unhittable knuckleball. The best story of all is that of Alfred, who lost an eye when he was playing catcher. Told that he would never play baseball again, the brothers patiently worked with Alfred to get him back on the field. Eventually he returned. “He was a pretty good catcher for a guy with one eye,” said brother Freddie.

The team succeeded for so long simply because “they stuck together.” Their camaraderie, tenacity and good spirits made them favorites all over the Northeast and New England, and in 1939 they were honored at the World’s Fair as the biggest family in New Jersey.

Though many details such as these seem quaint, evoking wistful memories of a vanished era is not the point of the story. The Acerra brothers were taught to serve others; in a family with 16 children, no one thinks only of himself. Those six brothers eligible to serve enlisted in the military and all fought in World War II. For years, they didn’t see each other, and baseball was essentially on hold.

All six brothers survived the war and returned to New Jersey to resume baseball. The Acerras joined the Long Branch City Twilight Baseball League and won the pennant four out of their six years in the league.

By 1952, however, baseball in America was changing. Jackie Robinson’s integration of the Major Leagues in 1947 had revolutionized the game, and the televised broadcast of more games meant that many of the local and regional leagues slowly began to fade away. The era of teams like the Acerras was over, but the memories remained.

In 1997, the Baseball Hall of Fame honored the Acerras with a special commemorative ceremony. The seven surviving brothers were in attendance, along with over a hundred family members. Following the ceremony, the Acerras’ bus broke down. The book concludes beautifully, with an image of three generations of the Acerra family playing baseball while they wait for their bus to be repaired.

Indeed, the entire book is beautiful, one of the most gorgeous children’s books I’ve seen over the past decade. Vernick’s prose is just the right tone for elementary school children, and is suited for both reading aloud and reading privately. The second- or third-grader who reads the book will be engaged by the story, of course, but will also learn important historical lessons about American society and history at mid-20th century. The values that the Acerras embodied are so well incorporated into the story that children will intuitively sense their importance.

But the most stunning aspect of “Brothers at Bat” is its visual style. The illustrations are wonderful. When I first saw the book, I was so captivated by the pictures that I snatched it from my son and savored the whole thing myself. Salerno is a gifted artist, and his style is wonderfully evocative of the period the book portrays. Salerno obviously pays tribute to the retro art work we associate with the Little Golden Books and the work of famed illustrators such as Lois Lenski, but as he was a student of the great Maurice Sendak, his style is not simply derivative. He channels his own family experiences and memories into work that is uniquely his own.

If we know one thing about the beautiful game of baseball in America, it is this: it endures. Vernick and Salerno’s book is a beautiful testament to how the game and its players reflect our deepest values. The Acerras valued family. They honored service. They treasured their faith. Reading selected obituaries and funeral notices of the 16 Acerra children reveals their lifelong commitment to their Catholic faith. “Brothers at Bat” expresses this dedication without ever becoming pious or didactic.

The 12 Acerras had a wonderful time as a baseball team, but they were even more successful in their personal lives. One senses that they quietly and dutifully went simply about the business of being decent people who lived for the good of others rather than for themselves.

David A. King, Ph.D., is associate professor of English and Film Studies at Kennesaw State University and director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church in Atlanta.