The treasure to be found in the ‘Picture Book of Saints’

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published January 21, 2016

The best present I received at Christmas was a re-gift.

On Christmas morning we had finished opening our gifts, and were preparing for a day of toy assemblage such as one might experience in a Victorian workhouse, when my older son Graham handed me a clumsily wrapped parcel.

“For you, Daddy,” he said. “From me.”

Graham had already given me a present—a money clip inscribed with the word “Dad”—that he had chosen at his school’s “Secret Santa” gift shop. The clip came without any currency, of course, and I suspect over the next several years of raising two boys that it will remain empty.

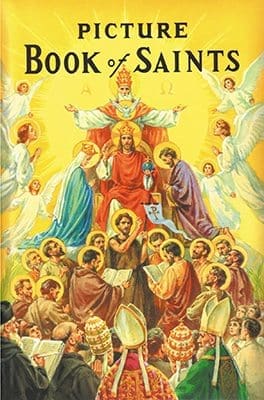

Surprised, I took the package and slowly unwrapped it. From beneath the torn paper and knotted ribbon, there emerged the face of God. Then the entire Trinity. And then in full pious glory, the Blessed Mother and St. Joseph and a vast host of angels and haloed holy men were revealed in splendor beneath a blazing sun.

My eyes teared. My son had given me the very book I had given him five years ago, the classic “Picture Book of Saints,” written by Rev. Lawrence G. Lovasik, SVD, and first published in 1962 by the venerable Catholic Book Publishing Corporation.

I was deeply touched that my son had passed on to me a gift that I had given him. How he could have afforded it, I had no idea. Where could he have gotten it? And as I opened the book to the presentation page, I saw the inscription his mother and I had made: “Presented to Graham Patrick King by Mama and Daddy, All Saints and All Souls 2010.”

Thus there entered into our family our own version of the widow’s mite. Having no means to purchase anything new, my son had given me all he had, the copy of a book he knew meant something very special to me and to him. I will now treasure the book always, and though I returned it to him, when he’s grown and gone, I will store it safely with his collection of plastic animals which will forever remind me of the wonder of his childhood.

I’m often asked to speak to Catholic audiences about the ways we can better engage our children in their religious education and give them a deeper sense of their Catholic identity, and I almost always recommend the “Picture Book of Saints.” After all, doesn’t every Catholic home with children have one? Even the large secular bookstores sell it. In nearly 25 years of teaching in both public and Catholic institutions, I have heard from scores of students who vividly recall the hold the book had on their own developing imaginations.

And yet for everyone who loves the book, there is someone who trembles at the very mention of it. The “Picture Book of Saints”—with its dedication to St. Joseph, its sturdy padded binding, its vibrant illustrations—that has for over 50 years come forth from the monolith of Catholic publishing in New Jersey, is actually one of the most controversial Catholic books for children ever written.

Long may it live, I say, and I’ll tell you why.

In his original foreword to the book, Father Lovasik addresses the young reader as “My Dear Friend,” and goes on to write, “God wants you, too, to become a saint. You do not have to be canonized to be a saint. You can be a saint by doing God’s will at all times. This means loving God with all your heart, and your neighbor as yourself.” What else, really, is there?

Beyond love, the child—and anyone else who seeks to deepen his spirituality—needs a few other gifts. We need a sense of awe, of wonder, of mystery. We need to conceive of the sacred, the holy, without being embarrassed or uncomfortable. We need concrete images of what we first perceive through natural revelation and our own human reason that then allow our imagination to bring forth a fuller conception of what is divinely revealed. We need to feel happiness, as well as sorrow. We need hope. And, as the old spiritual puts it, sometimes we do indeed need to tremble.

In her wonderful story, “A Temple of the Holy Ghost,” Flannery O’Connor writes of the developing Catholic faith of a young girl: “She could never be a saint, but she thought she could be a martyr if they killed her quick. She could stand to be shot but not to be burned in oil. She didn’t know if she could stand to be torn to pieces by lions or not. She began to prepare her martyrdom, seeing herself in a pair of tights in a great arena, lit by the early Christians hanging in cages of fire, making a gold dusty light that fell on her and the lions. … The lions liked her so much she even slept with them and finally the Romans were obliged to burn her but to their astonishment she would not burn down and finding she was so hard to kill, they finally cut off her head very quickly with a sword and she went immediately to heaven. She rehearsed this several times, returning each time at the entrance of Paradise to the lions.”

This is exactly the way the mind of a child works! O’Connor’s passage could in fact come straight from the pages of the “Picture Book of Saints,” which is full of vivid descriptions of the suffering so many saints endured. The entry on St. Agnes is particularly graphic: “While the crowd turned away from her, a young man dared to look at her with sinful thoughts. A flash of lightning struck him blind.” And, further, “After having prayed, she bowed her neck to the sword. At one stroke her head was cut off, and the angels took her soul to heaven.” This is balanced by the illustration of Agnes, who—true to her name—holds in her arms a lamb as she gazes serenely at the gentle reader quivering under the bed covers.

Throughout the book, the illustrations are evocative in their eeriness: St. Ignatius of Antioch prays among the lions who will soon devour him; St. Sebastian is bound to a tree, his body pierced with arrows, as he gazes toward heaven for mercy; St. Francis receives the stigmata in an image that looks like something out of Star Wars; and St. Michael and St. George slay Satan and the Dragon of Evil with powerful purpose.

Other images are overtly pious, but the better ones are gentle, and balance the violent scenes with pictures that are equally memorable: St. Dominic with his dog, St. Stanislaus Kostka receiving the host from an angel, St. Andrew with a stringer of fish.

Looking through the book as I wrote this column, I was struck by the pages my boys had marked: St. Ambrose with his beehive, St. Jerome at his desk with a great lion, and St. Benedict with his staff and raven. My younger son Nicholas was so taken with that raven that he dressed as St. Benedict for his school’s All Saints’ Day parade, complete with black bird his mother affixed to his cloak.

Accompanying the illustrations, each saint’s page includes a short prayer, a description of the saint’s patronage, and a brief biographical sketch. The book is designed so that a parent can easily read one or two entries to a child in just a few minutes, while a child who can read for himself could quickly become immersed in the short passages.

Ultimately, however, the pictures will be what endure in the imagination. Over the years, as the book is read and re-read, the text will also persist. Yes, it is pious, but the piety is informed with a sincerity that is genuine and loving. It’s obvious that Father Lovasik really cared about the faith of children. It’s also apparent that he knew that once the imagination is engaged, the intellect and spirit will follow.

Looking past the graphic tales of suffering that so appealed to Flannery O’Connor’s fictional child, there are invaluable lessons every child—and adult—should learn. “May we always lovingly serve the needy and the oppressed”; “Help us to seek equality for all races”; “May we live that which we profess”; and, most importantly, “Help us move forward with joyful hearts in the way of love.”

We live in a culture bent upon revisionism and skepticism. We live in the age of the “trigger warning,” when Red Riding Hood walks through the forest without a wolf and Mr. McGregor doesn’t bother with Peter Rabbit. We allow our children to learn more about “The Force” than we do their own Catholic faith.

When we dilute our stories to delete any sense of trembling, we also devalue the mystery and love that always conquer the source of our fears.

St. Cyril of Jerusalem often told his catechumens a brief parable: “The dragon waits at the side of the road; beware lest he devour you. We are going to the Father of Souls, but first we must pass by the dragon.”

The “Picture Book of Saints” endures as a classic Catholic children’s book because it understands this truth; in doing so, it respects the child and endows the child’s developing faith with excitement and awe as well as insight and empathy.

David A. King, Ph.D., is associate professor of English and Film Studies at Kennesaw State University and director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church in Atlanta.