‘Uncommon Grace,’ a documentary on life of beloved Catholic author, to debut

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published November 26, 2015

On the 13th of September, 1960, Flannery O’Connor finished a scolding but good-natured letter to her dear friend William A. Sessions—she called him “Billy”—by saying simply, “We’ll look for you Thanksgiving Day, and bring ‘A.’ with you.”

The letter appears in “The Habit of Being,” the collection of O’Connor correspondence edited by Sally Fitzgerald, and it—like the entire book—gives a fascinating glimpse into the daily life of one of our greatest writers.

“A.,” we now know, was the late Elizabeth “Betty” Hester, and Sessions has gone on to become one of the most important O’Connor scholars in the world, having discovered and edited her “Prayer Journal” and having written her forthcoming authorized biography.

Imagine the Thanksgiving dinner those three must have had! If Flannery had her way, she probably ate meatballs and turnip greens, which we know were among her favorite holiday foods.

These looks into the ordinary life of an extraordinary writer have distinguished the biographies that have been published, including the work of Jean Cash, Lorraine Murray and Brad Gooch, all of which have included revealing examples of O’Connor’s life at Andalusia in Milledgeville. Sessions’ book will be filled with personal reminiscence, since he knew O’Connor and her circle of friends so well.

Yet as fine as all these books are, something has been missing in O’Connor studies for decades. At last we have it: a full-length film documentary of Flannery O’Connor’s life, work and legacy as a Catholic artist.

Bridget Kurt, an Atlanta-based film producer and a Catholic has, along with Savannah filmmaker Michael Jordan and consultants Sessions and myself, completed a wonderful film that will become a fixture in O’Connor classrooms and a treasure for readers who have longed to see for themselves the important places and people associated with O’Connor’s short but vibrant life.

The project began as Kurt’s response to an ill-informed professor who had once told her that religion had almost no influence upon O’Connor’s work. Recalling that story, which Kurt has told me several times, still makes me cringe. Yet, even after the publication of “A Prayer Journal,” there are still no doubt readers and teachers who don’t understand the Catholic essence of O’Connor’s work and who remain ignorant about the author’s complete devotion to her Catholic faith. This film will correct that misconception.

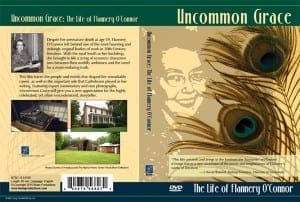

“Uncommon Grace: The Life of Flannery O’Connor” will take its place alongside other notable documentary films about Catholic writers, including Paul Wilkes’ “Merton: A Film Biography” and Win Riley’s “Walker Percy: A Documentary Film.” Though O’Connor has been treated briefly in film before, most notably in Ross Spears’ wonderful trilogy about modern Southern literature, “Tell About the South,” she has never been given the full documentary consideration she deserves.

If you are an avid reader of O’Connor’s work or an instructor who teaches O’Connor, you are probably overcome with excitement at the prospect of seeing the film. If you are simply a curious Catholic who doesn’t understand all the fuss, prepare to be enlightened. If you love Southern literature, and you’ve longed to see the landmarks and landscapes of O’Connor’s world, the time has come.

In a one-hour film, which is perfectly suited for classroom instruction, Kurt has created a masterful overview of a complicated life and a complex body of work. Yet the film is hardly a typical educational audiovisual aid guaranteed to induce sleep. Watching it is, in fact, a thrill; I’ve been teaching and writing and thinking about O’Connor for almost 25 years, and I couldn’t believe what I was actually finally getting to see.

If you’ve never been able to go to Savannah and visit O’Connor’s childhood home in Lafayette Square, here it is. If you’ve not seen Andalusia, in Milledgeville, the film takes you there. Even more remarkably, we see the years O’Connor spent in Iowa and at the Yaddo artists’ colony in New York. Almost every important site associated with O’Connor’s life is made visible.

There are close to a hundred images in the film that have never, or rarely, been seen. Everyone has heard about the Pathe newsreel that featured O’Connor’s childhood pet, a chicken she taught to walk backwards, but few people have seen it. It’s here. Manuscripts, ephemera, personal items; in shot after shot we see photographs and memorabilia that most O’Connor scholars have only imagined. Watching the film is like taking a museum tour.

Further, the film educates. The script is intelligent, taut and captures the essentials. Kurt’s own narration is perfectly suited to the story. The interviews, including conversations with Sessions, biographer Brad Gooch, and O’Connor expert Bruce Gentry of Georgia College, are revealing and engaging. We actually hear the story, told by Sessions himself, of the moment in the Milledgeville Holiday Inn when he opened a box and discovered the manuscript that became “A Prayer Journal.”

Perhaps most importantly, the film is Catholic. It features interviews with clergy, Catholic educators such as myself, and even the bishop emeritus of Savannah. The film makes no apology for O’Connor’s Catholicism and does not treat it merely as an aside as so much literary criticism has done. It foregrounds O’Connor’s faith and does so proudly. The film even feels Catholic, yet its Catholic atmosphere is never didactic and the film is as well suited for secular settings as it is for parochial schools.

Almost as important, the film captures beautifully a Southern sense of place, the quality integral to O’Connor’s fiction, so important that she referred to it as “the true country.” This is crucial. We aren’t just listening to people talk about the South, we are in the South.

While the film’s primary purpose is to cover O’Connor’s life, the empathetic manner in which the biography is revealed is balanced by an introspective and informative coverage of the literature. After viewing the film, the audience will understand O’Connor’s attitudes about her faith, her physical suffering, her region and her art. Further, that audience will be prepared to read O’Connor’s fiction with greater understanding and appreciation.

Flannery O’Connor often said that the most important task for the writer was to make the reader see.

In “Uncommon Grace: The Life of Flannery O’Connor,” we are at last able to see literally a panorama of a master storyteller whose work illuminates both the region and the faith we all share.

David A. King, Ph.D., is associate professor of English and Film Studies at Kennesaw State University and director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church in Atlanta.