Merton’s well-known meditations a respite from world’s chaos

By DAVID A. KING, PH.D., Commentary | Published August 20, 2015

The other day, a neighbor of mine hailed me on the sidewalk to report that he “can’t get no peace and quiet.”

It is August.

It is a time of commitments and obligations. It is a time of good intentions and resolutions. It is a time of appointments, and scheduling conflicts, and trying to be in three places at once. It is a time of new experiences and old routines. It is a time for registration, and volunteering, and pledging. It is a time of traffic, and a time of writing checks—many checks—for every conceivable program, and cause, and activity.

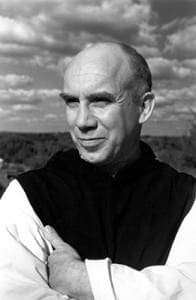

Trappist Father Thomas Merton, one of the most influential Catholic authors of the 20th century, is pictured in an undated photo. CNS photo/Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University

August is a difficult time.

If you are a parent, August is also a time when you crave tranquility and silence, and though it may seem impossible in the frenzy of the back-to-school mania, finding quiet time is essential.

Thomas Merton wrote that “In our age everything has to be a ‘problem.’ Ours is a time of anxiety because we have willed it to be so. Yet our anxiety is not imposed on us by force from outside. We impose it on our world and upon one another from within ourselves.”

Merton wrote this statement in his short meditation upon the necessity for solitary time, the brilliant and beautiful “Thoughts in Solitude,” which was written in the years 1953-1954 and first published in 1956.

The mid-1950s were a time of transition for Merton. He had been a monk at the Trappist Monastery of Gethsemani in Kentucky since 1941. In 1948, his autobiography, “The Seven Storey Mountain,” became a publishing and cultural phenomenon and made him famous in Catholic America. Ordained a priest in 1949, Merton was totally committed to his life as a monk and resigned to his growing role as the voice of Catholic reason in an increasingly turbulent Cold War society. Great books came quickly after “The Seven Storey Mountain,” including “Seeds of Contemplation” (1949), “The Sign of Jonas” (1953), and “No Man is an Island” (1955).

The popular image of Thomas Merton at this time was that of a rather quaint and curious monk, living an ancient lifestyle that few people understood, yet emerging from his silence year after year with profound and beautiful books that were destined to become classics of the canon of spiritual literature.

Yet Merton was busy. At times, he even felt overwhelmed. The life of a monk is not just “peace and quiet.” There are constant demands upon time and talent, and the routine of prayer and work can become as mind-numbing as our own regimented schedules of carpools and sports practice. Further, the monk has to adhere to his vows, including that of obedience, and he has to live in community with men he might otherwise never have chosen to be his companions.

At the same time Merton was adjusting to his now total immersion and commitment to monastic life, he served from 1951-1955 as the Master of Students. Now, not only was he obligated to write and publish, he also had the difficult task of teaching. Merton was a great teacher, and no teacher becomes great without hard work and sacrifice. Yet Merton accepted the teaching as an integral part of his vocation, and as he developed in that role, he was eventually named in 1955 the Master of Novices, a position he held until 1965 when he was finally allowed to live as a hermit.

It was during the early years of his work with the young monks that Merton’s own spirituality began to develop, flourish and evolve toward a much more mature understanding of prayer and the monastic calling. As he writes in “Thoughts in Solitude,” “The spiritual life is first of all a life. It is not merely something to be known and studied, it is to be lived.”

During the writing of the meditations that became “Thoughts in Solitude,” Merton was grappling with how to juxtapose and complement his commitment to community with his deepening need for solitude. What he reveals to himself in the book is therefore communicated also to the reader; Merton writes as much for us as he writes for himself. He not only tells us that solitude means nothing without community; he shows us that in our own hectic lives we too can discover and nourish spiritual maturity.

The book is divided into two distinct parts and also includes a short preface. In the preface, Merton is adamant that the book is neither “subjective nor autobiographical.” The book is not, he says, “intended as an account of spiritual adventures.” Further, Merton positions the meditations in our own chaotic world and argues that “society depends for its existence on the inviolable personal solitude of its members.” And these members, Merton argues, are not “mere cogs in a totalitarian machine.” We are all, each of us, human persons endowed with dignity and made in the image and likeness of God. Solitude helps us rediscover both our individual purpose and our love for God, and in turn allows us to realize again our place in a larger community. To be completely together, we must sometimes be completely alone. As Merton writes, “to be an acorn is to have a taste for being an oak tree.”

The book proper, however, reminds us that solitude is not merely being “alone.” Genuine solitude means complete communion with God, and complete trust in God, which the book’s two primary sections reveal. Part One is titled “Aspects of the Spiritual Life,” and Part Two is titled “The Love of Solitude.” The titles do not do justice to the meditations within each section.

“Thoughts in Solitude” is best read as a devotional, a day-by-day reading of the meditations in each section. Almost every meditation contains gems: “This, then, is our desert: to live facing despair, but not to consent. To trample it down under hope in the Cross;” “To be grateful is to recognize the Love of God in everything He has given us—and He has given us everything;” “Reading ought to be an act of homage to God;” “Violence is not completely fatal until it ceases to disturb us;” “The sky is my prayer, the birds are my prayer, the wind in the trees is my prayer, for God is all in all.”

As with almost everything Merton wrote, the language of “Thoughts in Solitude” is beautiful. Yet, paradoxically, Merton actually urges the reader seeking true solitude to understand language not as an end in itself, but as a key to deeper, unspoken truth: “the reality which is expressible in language is found, face to face and without medium, in silence.”

Merton argues that in an information age where most language has become incomprehensible and meaningless, we will only be able to understand anything important if we first learn to embrace the mystery of silence.

Embracing silence to find meaning in a chaotic world is not easily done. It demands trust, a complete abandonment of self to the love and will of God. Indeed, trust might be the greatest theme of this short book, and it is trust that is at the center of the most famous passage in “Thoughts in Solitude.”

In Part Two, Section II, Merton simply writes a plea to God. Merton himself does not call the passage a prayer, but that is what it has become. Along with the famous “Fourth and Walnut” epiphany from “Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander,” this passage—which begins with the words, “My Lord God, I have no idea where I am going.”—has become perhaps the most quoted excerpt from Merton’s writing, and it is universally beloved as one of our most beautiful prayers. As you move through August, and into the fall, and settle into the gift of the waning days of Ordinary Time that precede Advent, keep this prayer that Merton discovered in silence and then, as he had to, shared with us.

From “Thoughts in Solitude”

My Lord God, I have no idea where I am going. I do not see the road ahead of me. I cannot know for certain where it will end. Nor do I really know myself, and the fact that I think I am following your will does not mean that I am actually doing so. But I believe that the desire to please you does in fact please you. And I hope I have that desire in all that I am doing. I hope that I will never do anything apart from that desire. And I know that if I do this you will lead me by the right road, though I may know nothing about it. Therefore I will trust you always though I may seem to be lost and in the shadow of death. I will not fear, for you are ever with me, and you will never leave me to face my perils alone.

Thomas Merton

David A. King, Ph.D., is an associate professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and an adjunct faculty member at Spring Hill College, Atlanta. He is also the director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.