Documentary ‘Salesman’ reflects stark isolation of 1960s Americans

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published July 23, 2015

As revelatory and refreshing as the New Evangelization has been for contemporary Catholics, there are some who remain unsettled by the Church’s renewed emphasis on spreading the good news of the Gospel.

There are Catholics who wish to remain closeted in a solitary austerity, quietly attending Mass, going to confession, and living a life that exemplifies without fanfare their love of God and fellow humanity.

Many of these people simply want to be left alone to practice their faith as they always have, with private prayer and devotion and a contemplative approach to the sacramental life.

But there is a difference between being alone and being lonely. There is a difference between contemplation and apathy. In a changing Church, those who wish to know fully the joy of the Gospel must be open to communication, community and communion.

Of course, the changes we are experiencing in the Church now pale in comparison to those faced by adult Catholics in the wake of the Second Vatican Council. By 1969, when the liturgical reforms of Vatican II had been fully implemented, a large number of American Catholics simply did not know how to respond. Some left the Church. Many others retreated quietly into a solitude that left them isolated and alienated from the vibrancy that blossomed. Though they still went through the motions of their religious obligations, they did so from behind closed doors.

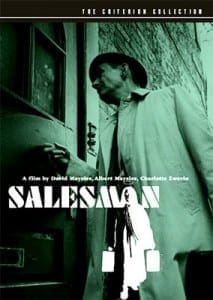

Those closed doors become quite literal in the classic American documentary film “Salesman,” which was released in 1969, and which captures perhaps better than any other film of the era the quiet desperation with which many Catholics, and indeed most Americans, were living their lives.

“Salesman” is both a prime example of cinéma vérité, or direct cinema, and the work of filmmakers Albert and David Maysles. The film becomes also a reflection upon isolation and loneliness and a criticism of the commodification of religion.

Brothers Albert and David Maysles were born and raised Jewish in Irish-Catholic Boston. When the two began making documentary films together, Albert handled most of the cinematography while David worked with sound. Their first great success was with a documentary called “What’s Happening! The Beatles in the U.S.A.,” for which they were given almost unlimited access to the Beatles on their first American tour. The innocence of that film was bookended by the tragic later film “Gimme Shelter,” which featured the stabbing of an audience member by Hells Angels at the Rolling Stones free concert at Altamont Speedway in San Francisco. In many ways, the Maysles filmed both the beginning and the end of the mythical 1960s.

The Maysles were assisted on “Gimme Shelter,” as they were on “Salesman,” by the brilliant editor Charlotte Zwerin. Together, the three filmmakers made the most accomplished American examples of the documentary style known as cinéma vérité.

Cinéma vérité existed in theory long before it became practical, but when the technological innovations of lightweight portable cameras and synchronous sound became more available and affordable, documentary filmmakers were able to realize the possibilities of the direct cinema approach.

Cinéma vérité proposes that the filmmaker record exactly what happens in real life; it insists upon objectivity over the personal subjectivity of the filmmaker, and it requires the filmmaker to refrain from any direction or manipulation of the subjects. Of course, this is almost impossible to achieve, for any decision related to filmmaking contains an inherent subjectivity. There is a person behind the camera, and that person can never really be completely separated from the process.

Still, the Maysles brothers work comes very close to achieving the “fly on the wall” ideal of the cinéma vérité approach, and it succeeds brilliantly in “Salesman.”

“Salesman” follows the daily lives of four door-to-door Bible salesmen and their manager. All of them worked for the American Bible Company, and all agreed to participate in the film for $100 each. The Maysles followed the men wherever they went and filmed exactly what happened. None of the men were actors; all were real salesmen who lived a life on commission. In fact, they were all amused that the Maysles wanted to make a movie about their mundane occupation. Who would want to watch a film about Bible salesmen?

But that is exactly what intrigued the Maysles about the subject. As Albert said, “Selling the Bible represented a metaphor of our time, which had ramifications reaching to every avenue of our culture.”

At the beginning of the film, each man is identified by both his Christian name and a nickname: Jamie Baker is The Rabbit; Paul Brennan is The Badger; Raymond Martos is The Bull, and Charles McDevitt is The Gipper. The manager, who speaks only in clichés such as “I am sick and tired of being sick and tired,” is Kenny Turner, and he demands success. Though he drives all the men, he is most hard upon Paul, The Badger, and the film becomes Paul’s story more than anyone else’s.

The door-to-door salesman has gone the way of the milkman and the doctor’s house call, but in the late 1960s, he was very much a part of American society. He peddled everything from vacuum cleaners to encyclopedias, even Bibles, and eventually he was bound to appear at your door.

Paul Brennan is one of these men, and he’s in a slump. His sales are down. He is separated from his wife. He is tired of the road, which takes him from snowy Boston to humid Florida in the same week. Most of all, his self-esteem is gone. Throughout the film, he derides his own Irish heritage. In a depreciating mock brogue, he says he “should have joined the force, got a pension,” and he sings “If I Were a Rich Man” like a litany. Like Willy Loman, he rides along on a smile and a shoeshine, and he would be pathetic if he didn’t seem to somehow possess some secret wisdom that he keeps hidden.

With the salesmen, we enter a 1960s Catholic America that is working-class, isolated, bleak, yet somehow strangely beautiful. Moreover, we enter a more universal America that is completely removed from our collective popular memory of the 1960s. There is no mention of Vietnam; no mention of the Kennedys or King; no mention of sex, drugs, and rock and roll. There are no young people at all, except for Boston children locked out of doors by their mothers and a Florida baby left alone in a high chair on a sweltering patio.

We come into the homes of strangers and feel as if we know them. “The Bible is the world’s best seller,” says the Rabbit, and with that opening pitch, we’re as captivated as the potential customers. At first, we’re tempted to think of these people as on the fringe of society, but they are not. They are the essence of society—housewives, laborers, pensioners; one is even a salesman himself, which he cruelly hides from Paul until after the Badger fails to close a deal.

Most of the attempts at sales fail. In one agonizing sequence, a woman who really wants the lavish Catholic family Bible simply can’t bring herself to justify an extra dollar a month. But most of the salesmen are good at what they do, and they close sales on everything from Bibles to Catholic encyclopedias. We see people make purchases only because they are happy to have the salesmen’s company. In one scene, we see a couple buy a Bible only because they want to show off their new hi-fi; the husband plays a Muzak recording of “Yesterday” while the wife signs the bill. In one of the very few subjective camera movements in the film, the Maysles let the camera linger on the husband in the doorway; he’s wearing a tank-top undershirt, smoking a cigarette, and listening forlornly to his stereo while his only real human contact of the day departs his driveway into the gloom.

It would be unfair to say that the salesmen don’t care about what they are selling; the Rabbit in particular seems proud of his Catholic identity. “Be sure to have it blessed,” he tells one customer of her new Bible, “or you won’t get the full benefit of it.” For the most part, however, Scripture and Catholic history are reduced to numbers on a sales tally, a source of pride to show off at the end of the day, back at a smoky motel room.

The customers, too, don’t seem to grasp fully what they’re buying, or what they really need. We imagine the Bibles and encyclopedias untouched on shelves for years after they were purchased; what they and the salesmen really need can’t be bought or sold.

David Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin died several years ago; Albert Maysles, who was most emotionally invested in “Salesman,” died just this March, but the film they made in that lonely year of 1969 remains a testament to our need for a genuine understanding of the Gospel, regardless of the covers in which it’s bound.

David A. King, Ph.D., is an associate professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and an adjunct faculty member at Spring Hill College, Atlanta. He is also the director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.