Hitchcock’s ‘Rear Window’ offers timely study of ever-present voyeurism

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published June 25, 2015

The Gospel readings for the past several days have come primarily from St. Matthew’s Gospel and the text that is one of the crucial cornerstones of the faith, the remarkable and challenging Sermon on the Mount.

Just a few days ago, we heard Jesus teach: “Stop judging, that you may not be judged. … Why do you notice the splinter in your brother’s eye, but do not perceive the wooden beam in your own?”

It’s not nearly as eloquent, but when Stella, a key character in Alfred Hitchcock’s great film “Rear Window,” says, “We’ve become a race of peeping toms. What people ought to do is get outside their own house and look in for a change,” she essentially echoes Jesus’ admonition that we should “remove the wooden beam from your eye first; then you will see clearly to remove the splinter from your brother’s eye.”

Hitchcock, a Catholic, must have been thinking of this passage when he came to make one of his great masterpieces in 1954. It was a time, he told Francois Truffaut, when he was “feeling very creative. … The batteries were well charged.”

Indeed, “Rear Window” marks the beginning of a run of brilliant Hitchcock films, many of which include his most profoundly Catholic subtexts. These films include “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” which is structured almost exactly like the liturgy of the Tridentine Mass; “The Wrong Man,” a docudrama which explores the deeply Christian theme of an innocent man wrongly accused; and “Vertigo,” Hitchcock’s most personal film and a profound meditation upon the mystery of the Communion of Saints.

Indeed, “Rear Window” marks the beginning of a run of brilliant Hitchcock films, many of which include his most profoundly Catholic subtexts. These films include “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” which is structured almost exactly like the liturgy of the Tridentine Mass; “The Wrong Man,” a docudrama which explores the deeply Christian theme of an innocent man wrongly accused; and “Vertigo,” Hitchcock’s most personal film and a profound meditation upon the mystery of the Communion of Saints.

I’ve written about “Vertigo,” which was named the greatest film of all time in the 2012 Sight and Sound poll, and I’ve written about Hitchcock as a Catholic artist, but “Rear Window” is a special film that deserves a separate consideration.

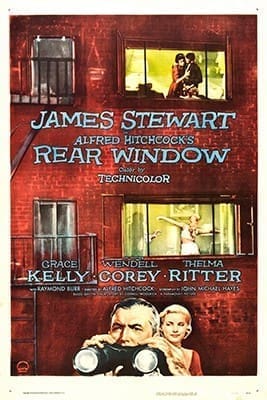

The plot of the film is simple, but as is usual in a Hitchcock film, the narrative and the entertainment value invite the perceptive audience into a more complex and rewarding viewing. L.B. Jeffries (James Stewart) is a photojournalist who has been injured while on assignment. Healing from a severely broken leg, Jeff is confined to a wheelchair in his Greenwich Village apartment. He has nothing to do but gaze out his window at the daily activities of his neighbors. Jeff is visited each day by Stella (Thelma Ritter), an insurance company nurse, and Lisa (Grace Kelly), his girlfriend with whom he has a troubled relationship primarily because of his fear of commitment. One evening, while staring out the window during a thunderstorm, Jeff notices his neighbor Lars Thorwald (Raymond Burr) making odd late-night trips to and from his apartment with salesman sample cases. Finding this to be very strange, Jeff spends the next day observing Thorwald polishing knives and saws and packing trunks. At the same time, Jeff notices that Thorwald’s invalid wife has apparently disappeared from the apartment. Jeff, along with Lisa and eventually Stella, becomes convinced that Thorwald has murdered his wife; he enlists the aid of a friend, a skeptical New York City police detective named Doyle (Wendell Corey), to solve the case. The film moves rapidly to a suspenseful and thrilling conclusion, which I’ll not spoil for those who may not have seen the movie.

That’s the simple part, and it’s fun. But it’s a much more provocative film if we consider it from the vantage of the Gospel and the brilliant insights Hitchcock has into visual perspective, relationships and love, and neighbors and community.

A film about the act of watching other lives

A deeper appreciation of the film begins with the understanding that Hitchcock is making a film about the act of watching, or looking, at other lives. On one level this makes the film a study of voyeurism; on another it allows the film to become an inquiry into the art of the cinema itself. The film begins from within Jeff’s apartment, and a long tracking shot establishes the setting of the courtyard apartments and the people who live there. We expect that the shot, coming from an interior, will be from the point of view of the occupant, but when the camera returns to the apartment, it rests upon the face of Jeff, who is asleep in his wheelchair. Immediately Hitchcock asserts that we are the ones looking; Jeff, after all, is sound asleep. We see for him what he cannot see. From the beginning, our perspective is linked with Jeff. We are implicated as voyeurs along with him. Indeed, once we see that Jeff is asleep and can’t see us, the subjective camera allows us to prowl through his apartment!

We are also characterized, like the waking Jeff will be, as an audience watching a film. “Rear Window” is actually a series of movies within a movie. Each apartment window becomes like a screen in a theatre. What do we see? A songwriter struggling to compose a hit tune. A lonely-hearted woman who acts out dates with imaginary gentlemen callers. A ballet dancer who performs suggestive exercises. A newlywed couple. A married couple with their beloved pet dog. A sculptor. And Lars Thorwald and his sick, nagging wife.

All these characters are performers in a series of vignettes, which represent the multiple possibilities for Jeff’s life. Jeff is an artist like many of his neighbors, and he lives in a community that is a haven for creative people. But more importantly, Jeff could have a life that resembles those that play out before him. If he commits to Lisa, he could live a life like the honeymooners that might evolve into either the happy marriage of the older couple with the dog or the miserable life of the Thorwalds. If he remains single, he could become the frustrated composer, or the suicidal Miss Lonelyhearts. Perhaps he could become the content sculptor, or the carefree dancer.

The point is that Jeff’s self-absorption feeds his fear of commitment, which underscores his genuine need for attachment, which he wrongly tries to fulfill by spying on his neighbors. Rather than committing to the woman who loves him, and instead of trying to know anybody, Jeff instead observes passively rather than acting. His binoculars and telescopic lenses are actually the extensions of a lonely and pathetic man, an invalid not because of his wheelchair but in spite of it.

What Jeff sees, what we see, is furthermore not to be trusted. For one thing, we can’t see everything, and Hitchcock delights in letting his camera obscure as much as it reveals. For another, we very quickly—along with Jeff—ignore our own faults and flaws by focusing instead upon the perceived sins of others. We don’t, after all, know whether or not Thorwald kills his wife.

Beyond this study in hypocrisy, the film is also a sad commentary upon the state of community. Anyone who has ever lived in an apartment house like Jeff’s knows the peculiar phenomenon of living among the lives of others who are separated from us by mere walls. We can live our lives without knowing anything at all about those above, below, or next to us. This alienation fosters anxiety and isolation, and Hitchcock clearly wants to make a statement about the need for genuine community. At one point in the film, Lisa wonders aloud, “whatever happened to that old saying love thy neighbor?” At another more chilling moment, a woman cries out to the entire courtyard, “You don’t know the meaning of the word neighbor! Neighbors like each other, speak to each other, care if anybody lives or dies, but none of you do.”

Finally, “Rear Window” is an indictment of our obsession with other people. Rather than addressing our own problems, we delight in the misfortune of others. A key moment in the film actually reveals a seeping sense of guilt about this flaw; Jeff sheepishly questions the ethics of his behavior, and Lisa admits that the two of them are like “frightening ghouls.” Though Hitchcock once said of himself, “I’m pretty much a loner. I don’t get involved in conflicts. I don’t see the point,” he knew how difficult it is not to look. He was keenly aware, especially as a Hollywood filmmaker, of the unhealthy fascination with the cult of personality. That fixation was a problem in the 1950s; today, it has become an integral part of our culture. We know everything about everybody; at least we are led to believe that we do.

But of course, we don’t ever know all there is to know, and at the heart of “Rear Window” is the acknowledgment that we do inhabit a world charged with mystery. Hitchcock’s genius is that he entertains us with a suspense story; the narrative grasps our attention, but the subtext manipulates our archetypal anxieties and desires to teach us something about ourselves.

Beyond the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus doesn’t give many other extended sermons in the Gospels. He does, however, tell lots of stories. Jesus called those stories parables, and Hitchcock’s best films reflect the aim and structure of the parables. “Rear Window” is never didactic; it shows us how we should live and urges us to be better than we are, and we see and remember the lesson because it is absorbed within a narrative masterfully assembled by a filmmaker whose Catholic identity and conscience are apparent in just about every shot.

You just have to know how to look for it.

David A. King, Ph.D., is an associate professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and an adjunct faculty member at Spring Hill College, Atlanta. He is also the director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.