Truffaut’s ‘The 400 Blows’ an enduring masterpiece of lost youth

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published May 29, 2015

The other day, at the end of the school year, I found myself wedged between other parents in a standing-room-only auditorium, watching my first-grade son receive an award for outstanding conduct.

And though I was proud of him, I found myself thinking about the day’s schedule at the Cannes Film Festival, and Francois Truffaut’s “Le Quatre Cents Coups” (“The 400 Blows”), and Antoine Doinel, the film’s main character and a boy who could never quite behave the way society dictates.

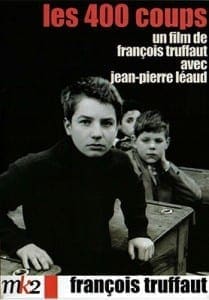

Truffaut’s film was a sensation when it premiered at Cannes 56 years ago. The film was awarded the Catholic Film Office Award and the Best Director Prize for Truffaut. Its success in France and the United States heralded the beginning of a Nouvelle Vague, or “New Wave,” in French cinema, and the film remains today an acknowledged masterpiece. Seeing it for the first time is for young people like a rite of passage; those who discover it later in life find themselves profoundly moved by its themes of lost innocence and dashed hopes.

The film, and its central character Antoine—brilliantly played by Jean Pierre Léaud—are inseparable from Truffaut himself. Truffaut was born in Paris in 1932, the illegitimate son of a Jewish father. He was adopted by his mother’s future husband and begrudgingly raised in a French Catholic family, at first by his grandmother and only later in his childhood by his aloof parents. He led a troubled young life, and in 1950 joined the French army, but his attempted desertion led to an arrest. His mentor, the Catholic intellectual and film critic Andre Bazin, was able to persuade the authorities to free him. Truffaut was now able to pursue a career in cinema, his one great love and perhaps the only place he ever really knew genuine happiness.

Throughout World War II and the Nazi occupation of France, Truffaut was denied access to films. Yet when the war ended, and Paris was liberated, France was flooded with movies, most of them American, that had not been available during the war. Like many French young people, including his friend and colleague Jean Luc Godard, Truffaut spent an obsessive apprenticeship in Parisian cinemas, where in a period of just a few years he saw thousands of films. Among his favorites were the movies by American directors, Hollywood outsiders such as Orson Welles, Nicholas Ray and Alfred Hitchcock.

Many of the films Truffaut and his friends saw had been ignored in America. In the United States, John Ford’s Westerns had been often overlooked as mere cowboy movies. The B-movies the French would give the name “Film Noir” were virtually ignored by American critics. In his adopted country, Hitchcock was simply “The Master of Suspense” and Orson Welles’ “Citizen Kane” disappeared almost immediately after its release.

But the French cinephiles recognized in these movies the indisputable personal stamp of legitimate artists. Led by the slightly older Bazin, who would soon die at the age of 40, they began writing serious academic pieces about cinema in publications such as Cahiers du Cinema. They formulated the Auteur Theory, which proposes that the director is the true author of a film. According to the Auteur Theory, which Truffaut introduced in a famous essay titled “A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema,” the truly authentic filmmaker was like an author; though he worked in collaboration with others, the finished film was the product of his unique personality and artistic vision and it bore his own individual stylistic traits and thematic concerns. Truffaut argued that most French directors had forgotten how to make a personal statement; he was fascinated by the American directors who created a personal cinema even within the strict boundaries of the studio system and the Production Code.

As so often happens in artistic movements initiated by the young, Truffaut and his contemporaries soon moved on from writing about movies to actually making their own. Most of their early attempts at short films were clumsy, but they had learned so much from seeing so many movies that they quickly improved. Along with the advancements in technology, which made on-location shooting easier, the young filmmakers were also aided by French producers who were eager for something new and fresh. The film that would affirm their trust in the young was “The 400 Blows.”

The title, translated literally from the French, is difficult to fully comprehend in English. It means something like our colloquial expressions “the last straw” or “raising hell.” The film follows a short period in the life of a young French school boy who is constantly in trouble. He mocks his teachers. He steals from his parents. He skips school. He smokes and drinks. He runs away from home. He lies. There are no conduct awards in Antoine Doinel’s future. There may not even be a future.

And, like Truffaut, the only happy moment Antoine has with his parents is when they go to see a movie.

Now, if any parent had a child who engaged in the litany of venial sins committed by Antoine, there would be no disputing that the child is “bad.” But Truffaut’s film makes us see that Antoine is not really the guilty one. Instead, he is the product of a society and a family that have failed him.

Antoine is an individual and a contemplative in an educational system that has no tolerance for critical thinking. In one of the film’s most touching moments, Antoine is assigned to write an essay about a pivotal moment in his life. He chooses to write about his grandfather’s death after being deeply moved by a passage from Balzac. He innocently plagiarizes Balzac, yet is so proud of his essay that he lights a votive candle for the author in his bedroom. The candle nearly burns down the apartment; the essay is failed as the work of an abominable plagiarist, and Antoine is suspended from school. That Antoine actually discovered the joy of great literature matters not at all.

Antoine’s parents are also to blame. They are rarely at home. The mother carries on adulterous affairs. The stepfather is abusive. Save for the trip to the movies, the family life is a sad routine of bad meals and loud arguments. The parents’ greatest concern is figuring out where and when to send Antoine away for holidays. Antoine wants their love, but they have none to give.

Eventually, after Antoine is caught stealing from his father’s office, the parents send him away to a reformatory. Funneled into the bureaucracy of the juvenile justice system, Antoine seems literally washed to sea; indeed that is where he ends up.

The moment is one of the most famous scenes in film history. At the end of the film, Antoine escapes from the reformatory soccer field. In a long, primarily uncut tracking shot, he runs and runs. Eventually, he reaches the beach. He keeps running. He comes to the sea, makes a few faltering strides into the water, then regresses back to the sand. He turns toward the camera, toward us. The camera zooms into his face, and the frame freezes. Antoine has nowhere to go; his life, like the film, seems over.

I assure you I have not spoiled the film for you if you have not seen it. The point of “The 400 Blows” is not to be absorbed in plot; it is to be absorbed in life. Further, the individual viewer’s interpretation of the film’s famous conclusion is just that—individual. Whatever your experience as a young person, a parent of a young person, or a person who once was young, that moment can only be fully understood from your unique perspective.

Yet the Catholic viewer, I believe, may find in the film’s conclusion a glimpse of hope. Rather than disappearing into the sea, Antoine is given the chance to confront the realities of life and the possibility of redemption.

Truffaut and Jean Pierre Léaud made four more films about Antoine Doinel—Antoine and Colette, Stolen Kisses, Bed and Board, and Love on the Run. I’ll not tell you what those movies are about, but I will tell you that they are not mere sequels, nor are they exploitative. Instead they reveal how much the filmmaker and the actor cared about the life of a character who transcends the screen.

Truffaut, like Bazin, had a brief life, and he died of a brain tumor at age 52. Though he did not live to make all the films he wanted to create, he left a legacy of work that deeply influenced young filmmakers all over the world. Additionally, he was the person most responsible for bringing Alfred Hitchcock the critical attention he deserved. Today, almost 50 years after its first printing, Truffaut’s long series of interviews with his hero Alfred Hitchcock remains a standard text not just for students of Hitchcock, but for film studies in general.

Truffaut identified with Hitchcock, and while Hitchcock was a privately devout Catholic, Truffaut was more marginalized, as he had never been fully accepted by his family. Yet he often worked with Catholic subject matter and had many friends who were priests. A month after his death, as he had directed, a Mass for his intentions was celebrated.

David A. King, Ph.D., is an associate professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and an adjunct faculty member at Spring Hill College, Atlanta. He is also the director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.