William Gildea’s ‘Colts’ sports memoir evokes Baltimore’s Catholicism

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published October 30, 2014

As I write this, the World Series is tied at 1-1; by the time you read this, the Series will be over, and we’ll know whether the Giants of the National League or the Royals of the American League prevail.

And a lot of Americans won’t care.

Though baseball remains a uniquely American pastime, it was eclipsed long ago by pro football as our country’s true national game.

Both Major League Baseball and the National Football League endure, in spite of controversy and in spite of changing times and tastes, because they are part of our national mythology. One day, perhaps, pro football might decline in popularity, but even if it does it will persist in our collective memory just as baseball does. It will endure because it, more than any other sporting league in this country, preserves and enshrines its iconic past.

Sometimes, however, it dishonors that past.

If you follow the NFL, you’ve probably noticed the commemorative patch that adorns the Colts’ never changing blue and white classic jersey—30 years in Indianapolis. That’s a good stretch of time, and there have been many wonderful memories made in Indiana over the last three decades.

For many football fans, those years don’t come close to the moments and memories the Colts made in their 30 years in their true country of Baltimore.

From 1953 until 1983, the Baltimore Colts reigned not only as one of the greatest teams in professional football, but as an emblem of the bond that sometimes exists between a team and the city it calls home.

Thirty years ago this year, in the middle of a snowy night in Maryland, moving crews hastily loaded a line of Mayflower vans and under cover of darkness departed the city that loved them as no other city ever loved a sports team.

So, the Colts had 30 years in Baltimore; now 30 years in Indianapolis, and for many people that’s the end of the story.

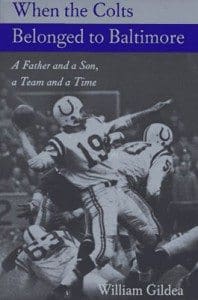

Yet there is another anniversary related to the Colts this year, and for people who might not even like football, but who love books and stories—especially love stories—it is an anniversary worth noting. This year marks the 20th anniversary of William Gildea’s wonderful memoir “When the Colts Belonged to Baltimore.” Subtitled “A Father and a Son, a Team and a Time,” Gildea’s book is not only one of the finest sports books ever written, it is to quote the New York Times’ initial review of the book “at once an elegy and a eulogy, every word from the heart.”

William Gildea is a fine sportswriter, but he is many other things as well. He is a native of Baltimore, and his love for and knowledge of his hometown is remarkable in an era when rootlessness is common all over a country of transplants whose suburbs are all the same. Gildea’s love for his hometown is inextricably linked with his love for his family, especially his father, who passed on to his son the gift of a sense of place. Finally, Gildea is a Catholic, and his Catholic identity—and the culture of Catholicism in Baltimore—is apparent throughout the book.

Of all the many things to love about the Baltimore Colts—the uniform that never changed, the iconic horseshoe helmet emblem, the glorious hodge-podge of Memorial Stadium with its row houses visible beyond one end zone, and the persistence of the Colts’ marching band that played on even after the team left town—the one that really resonates with Catholics is the fact that the team played its games not at the standard kickoff time of 1 p.m., but at 2 p.m., to ensure that fans could have equal time for both Mass and the ballgame.

Baltimore is of course a very Catholic city, and the Colts were a Catholic team. One of the Colts’ best-known head coaches, the brilliant Don Shula, had almost entered the priesthood. John Unitas, arguably the greatest quarterback to ever play the game, was a devout Catholic. So was Gino Marchetti, the Hall of Fame defensive end who broke his ankle in the 1958 “Greatest Game Ever Played” NFL Championship and stayed on the field, watching from the end zone, as the Colts won in sudden death overtime and a television audience of millions made the NFL the country’s new favorite game. And so was Alan Ameche, “The Horse,” whose final plunge over the goal line in that same game was memorialized in film and photographs that seem now like national icons.

Gildea doesn’t attempt to write a religious book, nor does he make the Catholic Colts into saints. Instead, he portrays the players as ordinary men, men who were a true part of routine Baltimore community life. They went to the same parishes as their fans; they drank and ate in the same bars and restaurants as the fans, and in the off-season they worked at jobs similar to other blue-collar Baltimore residents.

Gildea renders these men as integral to Baltimore life as the streetcars, the Catechism, Johns Hopkins, and Ogden Nash, and yet they were approachable, humble and genuinely grateful to be a part of the town’s culture.

It is unfathomable to imagine this kind of sincere connection between a professional sports team and its community today.

Gildea’s book, furthermore, isn’t so much a football book as it is a testament to why sport matters. It is as well a lamentation for a time gone by, and a moving testimony to the importance of place.

Georgia readers, and particularly native Atlantans over the age of 40, will find striking similarities between Gildea’s Baltimore and mid-20th century Atlanta. Both cities were provincial but always embraced boosterism in their attempts to become bigger and better. Both cities had a strong sense of regional culture evident in folkways, leisure and language. Both cities were proud, yet always dogged by the suspicion that they somehow weren’t good enough. Baltimore’s football team redeemed the town from its sense of inadequacy. The Falcons, well, that’s another story.

My father gave to me a deep love for Atlanta, his own hometown, much as Gildea’s father did for him. In the ‘70s, my dad often took me to Underground Atlanta on Saturday afternoons, and I got to climb under the abandoned boxcars and play with the organ grinder’s monkey. In 1972, perhaps the first time I ever saw my father cry, he took me to see the demolition of Terminal Station, one of the grandest buildings in the United States and now replaced by the blandness of the Russell Federal Building. He taught me why the Fox Theater was important, and why it needed to be saved. He rode with me, and got stuck in, the Pink Pig on the roof of the downtown Rich’s. And he taught me to love, curse, abandon and always forgive the Falcons.

Now of course, in Atlanta and all over America, things are different. Glass towers replace neighborhoods. Stadiums are corporate marketplaces in which the games often seem secondary to the onslaught of merchandising and spectacle. Teams come and go, with often no regard for their places and people.

But there was once a time, and that sense of the past and its connection to family and identity is what Gildea captures so evocatively in his book.

“Seated at Pop’s side each Sunday, I regarded this team as the center of our cosmos,” wrote Gildea. “Our love for each other grew as we kept on going to the games. Sunday was a ritual we shared. We’d go to Mass early and then drive together across the city to the stadium.”

Writing of the Colts’ greatest fan, Hurst Loudenslager, Gildea said, “The Colts loved Loudy like no group of athletes has loved a man. I’m pretty sure of that. Fans can be nuisances to athletes. Someone who dresses in a team’s colors and carries around a record player to play a fight song would seem eccentric at best. But the Colts appreciated Loudy’s sincerity. He was their friend.”

Near the end of the book, writing of Loudy’s death, Gildea confessed, “It’s hard to explain love between a man and a team.”

Of course, Gildea explained it throughout the whole of his beautiful book. It is a love in most cases connected to another generation, an older generation represented by a parent, relative, or friend who passes on something it cares about. It is a love connected to pride of place, to a sense of belonging to a town called home. It is a love connected to childhood, to the innocence of a moment in which the outcome of a Sunday afternoon football game could determine a week spent in either joy or anguish.

For William Gildea, the Colts will always belong to Baltimore.

For anyone who loves his Catholic identity; for anyone missing home; for anyone who has lost a parent, and for anyone who ever loved a team—any team—his book belongs to you.

David A. King, Ph.D., is an associate professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and an adjunct faculty member at Spring Hill College, Atlanta. He is also the director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.