Jack Webb’s classic police dramas depicted a Catholic view of right and wrong

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published August 22, 2014

For generations of American television viewers, the intonation “The story you are about to see is true. The names have been changed to protect the innocent” resounds in the memory as familiar as an oath, as comforting as a prayer.

Say those words to any middle-aged adult, and they can probably continue the litany: “This is the city, Los Angeles, California,” and conclude, “I carry a badge. My name’s Friday.”

The lines come from the iconic opening of the television police show, “Dragnet,” and are accompanied by sounds and images that are engrained in the popular consciousness—the panoramic views of Los Angeles; the LAPD badge, numbered 714; and one of the most memorable musical themes ever heard on television. If you know the show, you’re probably hearing the tune in your head right now.

And, if you know the show, you probably know all “the facts”: that the stories on every episode were indeed true, drawn as they were from actual Los Angeles police files; that the realism was the result of an almost obsessive attention to detail; that the perpetrators were always brought to justice by Jack Webb’s serious and stoical cop, Sgt. Joe Friday, for as the announcer informed us at the end of the episode, a trial was indeed held, and its outcome meted out the punishment that the criminals deserved.

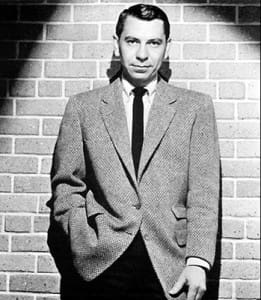

What you may not know is that the show’s creator, Jack Webb, was a Catholic whose imagination and attitudes about right and wrong were molded by a strict Catholic childhood, adolescence and college experience.

Jack Webb was born in Santa Monica, California, the child of a father he never knew and an Irish Catholic mother. Webb’s father abandoned the family before he was even born, and his mother raised him in the church. As a child, Webb attended Our Lady of Loretto Church and parochial school, where he served as an altar boy. Following high school, he chose to attend St. John’s University, the Benedictine college in Minnesota. At college, he studied art; he might have even sensed a vocation.

World War II changed Jack Webb. He did not do well in the U.S. Army Air Force, and he received a hardship discharge. To further support himself and his mother, he took a job as a radio announcer in San Francisco. The job led to Webb’s own show, then a series of radio-noir police dramas. These in turn led to the premiere of “Dragnet” on NBC radio in 1949. While the radio program continued to play until 1957, NBC also had Webb create a television version, which ran from 1952-1959. The show, which was produced by Webb’s own company, Mark VII Limited, had a revival in the late 1960s; these episodes, shot in color and co-starring Harry Morgan as Sgt. Friday’s partner, are the ones that most people remember today. The success of the later version of “Dragnet” led to two other memorable series, the police drama “Adam-12” and the fire rescue/hospital drama “Emergency.”

The importance of Jack Webb’s contributions to American television cannot be overstated. In “Dragnet,” Webb perfected the art of the realistic police drama. In “Adam-12” and “Emergency,” he created the prototype for contemporary police shows and hospital programs. Every popular television show in these genres, even the programs airing today, owes something to Webb’s genius.

Yet Webb’s more important contribution to American popular culture and our collective popular consciousness is equally enduring and more compelling. Webb didn’t just invent the television crime drama as we know it even today; he created as well a concept of “the police” that continues to shape, and challenge, our perception of what law enforcement is supposed to be.

So successful was Webb at creating this vision that at his death in 1982 he was given a funeral with full police honors, and the Los Angeles police retired Sgt. Friday’s badge number.

Webb had, first of all, an obsessive fascination with the police. This is certainly common; indeed, the success of the police genre owes much to the childhood wonder so many of us have about police and emergency workers. A highlight of every school year was for me, and now for my own sons, the visit of the policeman to school. What parent doesn’t cherish a memory of their child allowed to sit in a fire engine at the neighborhood station, or hit the siren in a parked patrol car?

When I was a schoolboy, my favorite elementary school lunchboxes were those decorated in “Adam-12” and “Emergency” motifs. Even if I couldn’t stay up late on school nights to watch the shows, I knew who the characters were. Our collective outpouring of support for police and fire personnel after the Sept. 11 attacks channeled not just our shared grief, but our sense of mystery and awe about the dangerous and thrilling occupations these men and women perform.

When the Rodney King affair occurred several years ago, and when the O.J. Simpson trial revealed the mistakes made by the LAPD, more than one pundit suggested that we needed Jack Webb’s police again. Such comments, however, missed a very important point. Webb’s policemen, like Webb himself, were fallible. They made mistakes both personally and professionally. But always—always—they addressed their errors.

Many episodes of both Dragnet and Adam-12 walked viewers through the excruciating process of internal affairs review boards; as Sgt. Friday said, “If a police force is to function effectively, it must not be held in suspicion by the community.”

Those words are certainly applicable to the recent tragedy in St. Louis. Yet they also represent a standard that is almost impossible to meet without occasional error.

Webb knew two crucial truths about the public’s attitudes toward some of its most important persons: educators, clergy and law enforcement. For one, they are almost always underpaid, unappreciated and misunderstood. We complain about our teachers, yet pay them nothing near what they deserve. We criticize our priests, failing to understand the overwhelming demands placed upon their time and the stress they must constantly endure. We deride, perhaps more than any other occupation in society, our police—until we need them.

This is the second truth Webb understood; we take those who nurture our intellect, our spirituality and our safety for granted until we suddenly find ourselves in trouble. To paraphrase Al Pacino’s detective in “Sea of Love,” “come the bad time, a cop is everybody’s daddy.”

While many people make fun of Webb’s shows, and parody in particular the character of Sgt. Joe Friday, Webb took the police very seriously. Every detail was as realistic as possible. Even when the story lines might be drab, Webb’s love for his subject is evident, so that the viewer is compelled to watch ordinary situations with rapt attention. Perhaps Webb’s greatest gift as an actor and director was that he could make us follow a bunko scheme with as much attention as a shoot-out.

Though Webb’s own personal life was hardly a model of adherence to Catholic teaching—his physical appetites were enormous; he had four marriages—it is obvious through his work how much he valued Catholic moral theology and the Catholic sense of justice.

Consider, for example, his production company credits that closed each episode of his programs. Two strong, sweaty hands (the hands of Jack Webb himself, many believe) grasp a hammer and chisel and pound into stone the name Mark VII Limited. There has been much conjecture over what Mark VII means and why Webb chose that as the name for his company. Dick Van Dyke claimed Mark VII was police parlance for “case solved;” most people claim the name means nothing at all.

I like to think it relates to the seventh chapter of St. Mark’s Gospel, which Webb would have known, in which Jesus says, “out of the heart of men proceed evil thoughts, adulteries, fornications, murders, thefts, covetousness, wickedness, deceit, lasciviousness, an evil eye, blasphemy, pride, foolishness: All these evil things come from within and defile the man.” And, surely, it must be more than coincidence that in the same chapter Jesus exorcises a demon from a young girl.

On “Dragnet” and “Adam-12” each week viewers confronted all of these sins. Yet they watched as well men and women who worked earnestly to overcome these faults. Most of the time, they succeeded. And it is that core belief, that a concern for the greater common good can effectively combat the persistence of evil, which makes Jack Webb’s police shows not just compelling drama, but Catholic as well.

David A. King, Ph.D., is an associate professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and an adjunct faculty member at Spring Hill College, Atlanta. He is also the director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.