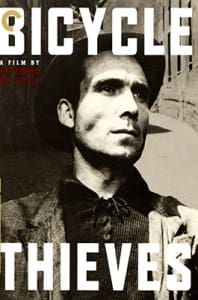

‘Bicycle Thieves’ a film masterpiece that voices ‘the cry of the poor’

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published June 26, 2014

Surely one of the most difficult challenges that faces any human being is finding the good even within circumstances that are tragic.

And certainly it is equally difficult to acknowledge that what for one person might be simply an inconvenience is for another indeed a tragedy.

These two great mysteries are at the heart of one of the greatest international films ever made, Vittorio De Sica’s masterful and unforgettable 1948 “Bicycle Thieves,” the film of which the great modern tragedian Arthur Miller wrote, “it is as though the soul of man has been filmed.”

That hyperbolic statement, surely one of the most audacious taglines ever contrived for any movie, may in fact be true, for in watching “Bicycle Thieves,” the viewer is forced to confront harsh realities that are universally relevant, true, and even beautiful.

In fact, when the Vatican assembled its list of the 45 most memorable films ever made, few people were surprised to see “Bicycle Thieves” among the titles. Should the Vatican ever release another such list, I would not be surprised to see the film included again. In fact, I would be dismayed if the film were ever to disappear from the list, for it is a perfect cinematic example of Jesus’ assertion that “the poor you will always have with you.”

“Bicycle Thieves” is about poverty, a desperate poverty that few of us will ever really know or see.

The film takes place in post-World War II Italy, in Rome. True to the aesthetic of Italian neo-realism—a film movement that sought to achieve social change through documentary realism, non-professional actors, and on-location shooting—De Sica’s film traverses all through Rome, from the suburban tenements to the teeming streets of the metropolis. When the film begins, a crowd of day laborers is waiting for a bureaucrat to assign them employment. The official shouts a name, “Ricci, Ricci.” Ricci is fortunate this day; a job is waiting for him, a good job. There is only one catch. Ricci must have a bicycle.

Promising the official that he does indeed have a bicycle, Ricci hurries home to find his wife Maria. He has a job, he says. All he needs is a bicycle. Maria strips the sheets from the bed; the sheets can be pawned to then retrieve Ricci’s bicycle from pawn itself. After paying even more interest on the pawned bicycle—it’s the first of the month, the pawnbroker explains—Ricci finally has the bicycle he needs. He reports to work, is given a uniform, and told to report the next day for the job.

On the morning of Ricci’s first day of work, De Sica shows us more of Ricci’s family. There is a baby, and a young boy, Bruno—two mouths to feed in addition to Ricci and Maria. Bruno is already working himself, though he’s only about 6 years old. He and Ricci leave home together; Bruno goes to his job at a small service station, and Ricci heads for his new occupation as a poster-hanger; he plasters walls with giant posters of film stars.

Ricci is quickly trained, and then he sets off deep into Rome to begin his work. He is happy. His movements and simple facial gestures reveal the honor and dignity of a man who is allowed to work for his own sustenance. While he is hanging a poster of Rita Hayworth, a young man in a German cap spies on him. It quickly becomes apparent to the audience that a crime is about to be committed. Working in cooperation with two other men, the young man leaps on Ricci’s bicycle and pedals away into the crowded streets. His fellow conspirators thwart Ricci’s attempt to catch the thief. In a matter of a few tense moments, Ricci’s bicycle is gone. Ricci’s life is gone.

In the first of a pattern of events that shapes the film, Ricci is not helped by the police. They are only annoyed bureaucrats. The theft of Ricci’s bicycle is simply that, the theft of a bicycle and nothing more. It happens all the time.

At the end of the day, Bruno is shocked to meet his father, arriving late, without the bicycle. That evening, Ricci approaches his best friend, who promises to help search for the bicycle the next day. Ricci, Bruno, and their friends scour all the flea markets and bazaars of central Rome. They search for anything—a frame, a bell, a seat. By the end of the day, the bicycle remains lost, but the thief is found.

Though the thief is found, there is nothing anyone can do about it. There is no bicycle, so there is no proof. No one can help Ricci. He’s failed by the police again. He’s failed by a charitable organization. He’s failed even by the Church. Ultimately, he’s failed by the community of the thief, who degrade themselves by subverting honor to aid one of their own, who like Ricci is also poor.

In one of the most remarkable endings of any film, Ricci and Bruno leave the thief’s neighborhood. There is nothing to be done. As they head home, they pass the national soccer stadium. Ricci confronts giant statues outside the arena, iconic models of values that he can never hope to attain. And then, around the corner from the stadium, Ricci sees it—a lone bicycle, unguarded on an empty street. The viewer knows what Ricci wants because the viewer wants it himself: we want that bicycle. To underscore our shared desire with Ricci, De Sica shows us images of huge ranks of bicycles, chained and waiting for their owners to leave the stadium. He shows us a bicycle race pass by Ricci and Bruno sitting forlornly on the curb, as Ricci wrestles with his conscience.

Then Ricci acts. He tells Bruno to go home on the streetcar. Ricci goes to steal the bicycle; he too will become a bicycle thief in this endless chain of poverty where criminal and victim constantly shift roles. In a great moment of dramatic irony, Bruno misses the streetcar, and thus is present when Ricci steals the bicycle and is then apprehended and humiliated in the street. Ricci is only spared a trip to jail when the bicycle owner takes pity on the weeping Bruno. In the last shot of the film, Bruno and Ricci disappear into the throng of anonymous souls, their sad exit into the gloom softened only by Bruno’s simple gesture of taking his father’s hand.

I’ve seen the film I’ve just described probably 50 times. There are people who watch it and are immediately moved; they understand that truly, as Arthur Miller argued, “the common man is as apt a subject for tragedy in its highest sense as kings were.”

Yet many people are also callous; it’s just a bicycle, they say. What’s the big deal? Still more say simply, it’s depressing, and who wants to be depressed?

Pope Francis recently remarked that “among our tasks as witnesses to the love of Christ is that of giving a voice to the cry of the poor.” That is what “Bicycle Thieves” does.

The man who plays Ricci was not an actor. He was a working class Italian who had brought his son to De Sica to audition for the film. The man, Lamberto Maggiorani, was himself poor. His Italian dialect was so difficult to understand that another man’s voice had to be dubbed for the soundtrack. Maggiorani became instantly one of the most iconic faces associated with poverty in the history of film. He also became one of the movies’ most memorable portraits of dignity in the face of suffering.

“Bicycle Thieves” works as valid tragedy because, as Miller asserted, the effort to preserve personal dignity is crucial to tragedy.

Pope Francis puts it another way: “poverty calls us to sow hope.”

“Bicycle Thieves” is not “depressing.” It is full of moments of hope—the help of friends, the love of family, the belief in the possibility of the miraculous. All these moments redeem Ricci and Bruno from bathos. They lead toward what Aristotle claimed tragedy must do; they lead to a sense of catharsis, the cleansing away of the tragic emotions of pity and fear.

Most of us will never know the cruel effects of poverty. We will not understand how life hinges upon something as simple as a bicycle. We won’t see that a simple restaurant meal of wine and toast can be like a banquet. We will not know what it means to cast away honor in the hope of preserving a sense of honor. De Sica’s film reveals all of this for us.

In doing so, “Bicycle Thieves” is a modern masterpiece that allows us to understand, as Pope Francis knows, that “to love God and neighbor means seeing in every person the face of Jesus.”

David A. King, Ph.D., is an associate professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and an adjunct faculty member at Spring Hill College, Atlanta. He is also the director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.