Children’s book illuminates Catholic faith

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published December 19, 2013

I got passed over by the Secret Santa this year.

I got passed over by the Secret Santa this year.

You probably know how this works. Your child is allowed to shop for small gifts at school; it’s a chance for the child to learn how to choose and give gifts to others, and while the presents are usually pretty cheap, they often end up being treasured by the parents who receive them. I once gave my father a plaster Georgia Tech Yellow Jacket (he was a Tech fan in a house full of Bulldogs) and it stayed on his bedroom dresser for 20 years.

But my 6-year-old Secret Santa passed me by.

He was so busy choosing gifts for his mother and little brother (which I had encouraged him to do) that he forgot about Daddy. When he got home from school yesterday afternoon, he carefully put all his wrapped and tagged gifts under the tree. There were presents for Mama—even a ring—and presents for little brother, and, well, nothing for Daddy.

My son sobbed the tears that only a 6-year-old boy can cry, those great big crocodile tears of an innocent child. He tried to smuggle a comic book for me under the Christmas tree. “It’s OK,” I said, “really.” He tried to give me a cardboard piggy bank. Then he put a cracked wise man from one of our many broken Nativity scenes in the piggy bank. Again I refused the gifts. “It’s alright,” I explained. “You’ll have other chances.” But still the tears came, and I was deeply touched to watch my son confront the complicated emotions of shame and sorrow.

My boy didn’t realize, of course, that he had actually given me the best gift of all. His sadness in having forgotten my cheap present resulted in a display of love for his father that I don’t think I will ever forget. In focusing on the material, he overlooked the more meaningful spiritual gifts of sincerity and love.

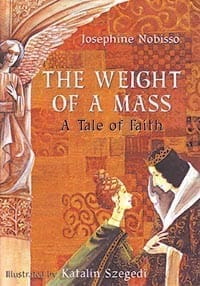

I thought about this important lesson when I read again Josephine Nobisso’s marvelous picture book “The Weight of a Mass: A Tale of Faith.”

The American picture book is a national cultural treasure, though I suppose all cultures produce illustrated books for children that become cherished touchstones of youth. In fact, for me one of the greatest joys of parenthood has been introducing, and revisiting, the beloved picture books of my own childhood. Reading Judith Viorst’s “Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day,” or Maurice Sendak’s “Where the Wild Things Are,” or Ezra Jack Keats’ “The Snowy Day” to my own children has allowed me to enter again that marvelous world of childhood imagination where some of the most important lessons we will ever learn are encountered for the first time.

So I’ve spent a lot of time searching for meaningful Catholic children’s books that will teach my boys not only the importance of art and imagination but also the gift of their faith.

There are good books out there; my older son adores, for example, the classic “Picture Book of Saints,” published for over 50 years by the Catholic Book Publishing Corporation. In fact, I suspect my son—like generations of children before him—will forever imagine Heaven as it is depicted on the book’s frontispiece.

And there are books that while not explicitly Catholic are so obviously under the influence of Catholic theology and identity that they must be considered classics of religious literature; C. Collodi’s big “Pinocchio” of 1925, reprinted in 1969 and 1989 with its iconic illustrations by Attilio Mussino, immediately comes to mind.

But sadly, there are also a slew of books that are didactic, edifying and so overly pious that children are immediately suspicious of them. Children, I have learned, are actually quite wise. They know, as Jesus knew of them, that the really important truths are much more compelling when they are expressed in myth and narrative, when they are explained in stories.

There are exceptions to the heaps of saccharine children’s books of faith, and I should add, these books also provide an antidote to the abundance of secular “Christmas” books that should all be consigned to the ash heaps.

Among these exceptions is Nobisso’s “The Weight of a Mass: A Tale of Faith.” Like all truly great children’s literature, the book engages children even as it also teaches the adult reader.

The story, which Nobisso adapts from a European folk tale, concerns a poor widow who enters a wealthy baker’s shop to beg for a crust of bread. In exchange for the bread, the old woman promises to offer her Mass for the baker. The Mass she is to attend is in fact a wedding Mass of a King and his soon-to-be Queen. The baker is not impressed. In fact, he scoffs at the very idea of Mass, and mocks it as a ritual intended only for the sick and old. The kingdom, as the story explains, “had grown cold and careless in the practice of their faith.”

As the baker’s wealthy customers buy lavish pastries and other expensive goods, the baker cruelly decides to deride the beggar woman publicly. On a slip of paper, he writes the words “One Mass.” He places the paper on one side of a scale. On the other side of the scale, he begins to place bread, cakes, and pastries, but to his astonishment, the scale does not move. In a series of wonderful pages, illustrated by the award-winning Hungarian artist Katalin Szegedi, the baker rushes around his shop, piling the scale higher and higher. Still, the scale does not move.

The wealthy customers are incredulous. The baker must be a cheat! His scales are off! The baker insists the scales are honest; they’ve just been inspected. Yet when the baker fills the scale with an enormous amount of goods, and places the slip of paper again on the other side, the note actually levitates the opposite scale. As the baker’s son exclaims, “The Mass intention weighs more than these!” “This can’t be,” protests the baker, yet even the royal wedding cake is outweighed by the “One Mass.”

As the cathedral bells began to toll to announce the beginning of the Mass, all the wealthy shoppers who had previously no intention of attending the Mass begin to make their way to the church. Only the widow remains. The baker promises that the old woman will be forever welcome in his shop, “she’ll never go hungry again!” But the widow is content with the small piece of bread she wanted in the first place; it is, after all, all she really needs.

The story is loaded, of course, with all sorts of connections to Catholic Christianity, particularly the real meaning of the Eucharist. The bread at the baker’s shop, the miracle that occurs on a wedding day, the triumph of simplicity and poverty in the face of the superficial and the rich all correspond to the fundamental lessons of the Gospel and Catholic teaching.

Nobisso even includes a summary of some of the story’s primary Catholic symbols, and the book concludes with an author’s postscript that explains the original fable and some of the miracle’s other consequences (which I’ve not mentioned here, so as not to spoil any surprises). Most impressively, Nobisso concludes her postscript with a quote from the Catechism of the Catholic Church: “The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass—the Eucharistic Celebration—is the priceless source and summit of the Christian life because in it, Christ himself is truly present. In its unfathomably deep richness lies the perfect fulfillment of Jesus’ command to repeat His actions and words until He comes.”

The adult reader will appreciate these explicit reminders. The child who listens to the story and looks at the pictures doesn’t need them. He or she will know immediately, and intuitively, the truth embedded in the narrative and the art.

So my son, like the baker and his wealthy customers in their jaded kingdom, learned a lesson from the Secret Santa shop. It’s not the material gifts that matter, but the gifts of the spirit that really sustain us. The mystery and the miracle of the Mass are so often overshadowed, not just at Christmas but throughout the year, by things that don’t really mean anything.

Josephine Nobisso’s simple but beautiful book is a wonderful reminder of the gift of the Eucharist, and while it will make a wonderful Christmas present for children and their adult readers, it is a book that merits reading at any time of year when we need to focus on the essence of our life and our faith.