F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Identity ‘Shaped’ By Catholicism

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D., Commentary | Published June 20, 2013

They appear each summer about this time, just as students are settling in to the relaxed routines of summer vacation. They are in the giant chain stores, the independent bookshops, the public libraries. To students, they probably seem mocking and cruel. Spread out on table upon table, they suggest that this year, there will be no respite from learning, no escape from knowledge.

Yes, summer reading season is upon us. Across the archdiocese, students in all sorts of schools—parochial or public, private or at home—are supposed to be reading. Amidst all the books the students are requested or required to read stand the perennial canonical choices. Among them, you can be sure, is

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s brilliant novel “The Great Gatsby.” I suspect Gatsby will be even more widely read this summer since a new film adaptation of the novel is currently in movie theaters.

I first read “The Great Gatsby” when I was in the 10th grade, and I’ve gone on to re-read it and teach it perhaps more than any book I’ve ever read. There are parts of it that I know by heart, passages that I often find myself quoting. There are images in the novel that are part of my being, that are in fact part of our collective national consciousness.

My sophomore English teachers in high school did a fine job of teaching the novel, and they approached it as teachers still do. From a historical perspective, Gatsby is held up as a product of the Jazz Age, the gilded era of avarice and folly that preceded the fallout of the Depression. For further context, the novel is treated as a product of the Parisian renaissance that occurred in the aftermath of the First World War when young American expatriates flocked to the Left Bank. When these historical lessons are finished, Gatsby becomes a handy means of teaching fundamental moral principles: don’t drink too much; don’t be greedy; don’t commit adultery. Further, the novel is an excellent introduction to the larger themes of American literature, particularly because of its obsession with the past and its emphasis upon innocence lost. And the book is a case study in how to write a great novel, for “The Great Gatsby” is indeed one of our country’s very best.

My sophomore English teachers in high school did a fine job of teaching the novel, and they approached it as teachers still do. From a historical perspective, Gatsby is held up as a product of the Jazz Age, the gilded era of avarice and folly that preceded the fallout of the Depression. For further context, the novel is treated as a product of the Parisian renaissance that occurred in the aftermath of the First World War when young American expatriates flocked to the Left Bank. When these historical lessons are finished, Gatsby becomes a handy means of teaching fundamental moral principles: don’t drink too much; don’t be greedy; don’t commit adultery. Further, the novel is an excellent introduction to the larger themes of American literature, particularly because of its obsession with the past and its emphasis upon innocence lost. And the book is a case study in how to write a great novel, for “The Great Gatsby” is indeed one of our country’s very best.

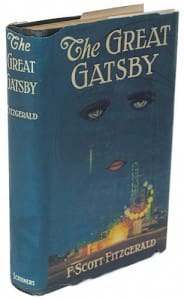

So, “The Great Gatsby,” complete with its famous dust jacket image, definitely deserves a place on the summer reading table. Along with “A Separate Peace” or “The Catcher in the Rye” or “The Sun Also Rises,” the book is a fixture on the high school summer reading lists.

That is a good thing. Yet what is unfortunate is how much is overlooked regarding the man who wrote the novel.

F. Scott Fitzgerald was a Catholic. He was in many ways a “bad Catholic,” to use Walker Percy’s tongue-in-cheek phrase, but he was a Catholic nonetheless. He was born and baptized a Catholic and lies buried as a Catholic. Where his soul is now is anyone’s guess; James Dickey even wrote a poem called “Entering Scott’s Night” that imagines Fitzgerald in purgatory.

Most people, even Catholics, don’t know that Fitzgerald was a Roman Catholic. They know that he was an alcoholic. They know he was married to the beautiful and doomed Zelda. They know that he worked furiously to make a living as a writer, whether it was for Hollywood or popular magazines. Yet few people know that Fitzgerald’s Catholicism shaped his personal identity and in many ways his vision of the United States.

Fitzgerald was born in 1896 in St. Paul, Minn., and named after his distant cousin, Francis Scott Key, the composer of “The Star Spangled Banner.” Most of his childhood was spent in Buffalo, N.Y., where he attended two Catholic schools. Fitzgerald was so precocious that one school allowed him to attend only a half day of school and permitted him to study independently. Further schooling took place in St. Paul and Hackensack, N.J. Fitzgerald attended college at Princeton, but left in 1917 to join the Army. While training near Montgomery, Ala., he met Zelda at a party. They were married at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York in 1920. Their only child, Frances, was born the following year. After his celebrated stay in Paris, Fitzgerald published “The Great Gatsby” in 1925. Fifteen years later, after an agonizing marriage, a series of publishing disappointments, and deteriorating health due to his alcoholism, Fitzgerald died in Hollywood in 1940 at the young age of 44.

Before his death, Fitzgerald had made it known that he wished to be buried in Baltimore, which he considered his ancestral and spiritual home. Yet because of his drinking, his sordid novels, and his marriage to a Protestant, the Church would not permit him to be buried in a Catholic cemetery. Fitzgerald was buried instead in a Protestant cemetery in Maryland.

For over three decades Frances had struggled for permission to move Fitzgerald’s body to St. Mary’s Catholic Cemetery in Baltimore, and in 1975 the request was finally granted. Fitzgerald was at last where he had wanted to be, in sacred Catholic ground. Yet the students who continued to read Fitzgerald’s novels throughout the decades after his death knew little, if anything, about his religion. One of Fitzgerald’s early biographers essentially declared that Fitzgerald’s Catholicism was irrelevant.

Hindsight and some recent discoveries have shown the fallacy of that assertion.

Though Fitzgerald admitted to the critic Edmund Wilson that “I am ashamed to say that my Catholicism is scarcely more than a memory,” his choice of words implies that he still identified with the faith, that he missed it, and that it obviously had shaped his imagination. Perhaps Fitzgerald himself forgot for a moment one of the great lessons to be learned from his work: the things that mean most to us persist in the memory.

Like much great modern Catholic art and literature, the references to Catholicism in Fitzgerald’s work are usually subtle. The best example, as many people have suggested, is the wonderful image of the eyes of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg, staring across the wasteland of ash heaps from a billboard in “The Great Gatsby.” As a symbol, the eyes become like the gaze of God surveying the modern world.

Yet there are three overt references to Catholicism in Fitzgerald’s short stories, the fiction he wrote primarily to make a living. One story, “Absolution,” is a vivid portrayal of the Church before Vatican II, which demonstrates the discrepancy between the letter and spirit of the law. Another story, just discovered and recently published in The New Yorker magazine (6 August 2012), is “Thank You for the Light,” a one-page story about the Virgin Mary interceding for a woman who desperately needs a cigarette. It’s a funny story. It also affirms the possibility for the miraculous.

A final story, in the collection “Flappers and Philosophers,” is “Benediction,” which is about a young woman who stops to visit her brother in a Catholic seminary while she is on her way to meet a lover. One exchange in the story is particularly telling. The woman, Lois, has admitted to her brother that her Catholicism no longer matters to her. And yet her brother replies, “I’m not shocked, Lois. I understand better than you think. We all go through those times. But I know it’ll come out all right, child. There’s that gift of faith that we have, you and I, that’ll carry us past the bad spots.” Indeed, the brother requests, “I want you to pray for me sometimes, Lois. I think your prayers would be about what I need.”

In the wake of “The Great Gatsby” movie release, St. Mary’s Cemetery in Baltimore reports a huge increase in visitors to Fitzgerald’s grave. More people are reading Fitzgerald again, and not just students who are working their way through summer reading lists. Perhaps in all the recent buzz about Fitzgerald, someone should pray for him. I think it is exactly what he needs.