Lou Gehrig, Gary Cooper and ‘The Pride of the Yankees’

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D. | Published April 16, 2020

“Don’t think I am depressed or pessimistic about my condition at present. I intend to hold on as long as possible and then if the inevitable comes, I will accept it philosophically and hope for the best.”

Henry Louis Gehrig, one of the greatest baseball players to ever play the game, wrote those words not long before his death—at the age of 38—from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) in 1941.

Oh, that we could all have that same sense of calm and stoic acceptance now.

We all have a lot to feel sorry for. The pandemic that only a month ago seemed an oddity, a distraction, has ballooned into an international public health and economic nightmare. Writing about it seems almost futile.

At times of futility and depression, we often turn to sport to divert attention from our troubles. Now, there are no sports.

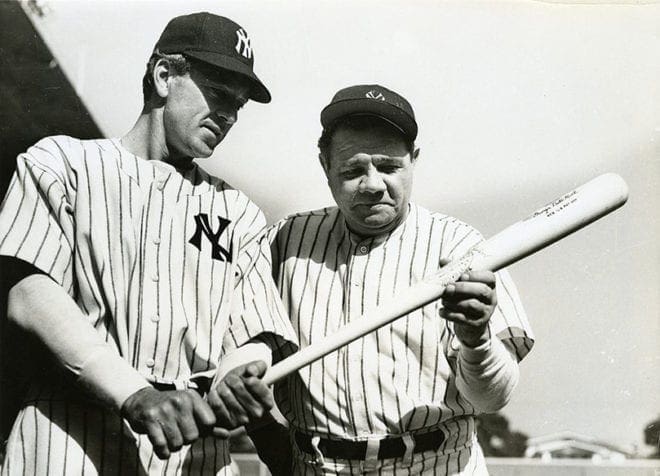

Babe Ruth, right, with actor Gary Cooper in the 1942 film “The Pride of the Yankees,” about the life of Lou Gehrig.

Regular readers of my column know that almost every spring, I write about baseball, which was supposed to have started by now. My family and I have tried to compensate. Rather than visiting our local card shop, which of course is closed, we bought this season’s baseball cards from Amazon. I’ve been re-reading Jimmy Breslin’s wonderful account of the New York Mets’ inaugural 1962 season, “Can’t Anybody Here Play this Game,” and Roger Kahn’s classic book about the Brooklyn Dodgers, “The Boys of Summer.” And we’ve been watching baseball movies—lots of baseball movies, from “The Bad News Bears” to “The Natural,” “Field of Dreams” to “Fever Pitch,” “42” and “61” and the greatest of them all, the 1942 classic “The Pride of the Yankees,” which is the story of Lou Gehrig.

The grace to be thankful

Lou Gehrig, “the Iron Horse,” was the child of German immigrants who was born and raised in New York City and attended college at Columbia University. In 17 seasons between 1923-1939 with the New York Yankees, Gehrig played in 2,130 consecutive games, a record that stood for nearly 60 years until it was surpassed by Cal Ripken Jr. Undoubtedly one of the most gifted ballplayers of all time, Gehrig’s life—like that of Roberto Clemente—was distinguished as well by his unsung accomplishments off the field, including public service and a devoted loving marriage. Gehrig remains a model of character and integrity, admired for his values and ideals as much as for his lifetime batting average of .340.

Near the close of the 1938 season, Gehrig’s play suddenly seemed different. He felt tired. His speed slowed. His power flattened. Though he reported for spring training in 1939, he struggled with all aspects of the game. On May 2, Gehrig told Yankee manager Joe McCarthy that he was taking himself out of the lineup. Gehrig never played baseball again.

Gehrig reported for a series of tests at the Mayo Clinic that revealed a tragic diagnosis of ALS, which meant the onset of paralysis and certain death. He could expect to live little more than three years.

On the Fourth of July in 1939, the Yankees held a day of honor and appreciation for Gehrig. At that event, following the accolades and tributes from his peers, Gehrig approached the microphone to say a few words. His few words became one of the most memorable speeches of the 20th century.

Gehrig began in a calm, steady voice, and utilized just the right cadence, with effective and poignant pauses: “Fans, for the past two weeks, you’ve been reading about a bad break. Today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth.”

Gehrig goes on to explain the luck, the blessings, the honor of his teammates over the years; the managers for whom he played; his parents who instilled in him a strong work ethic and a love of education; his wife, who was truly the love of his life. He then concludes, “I might have been given a bad break, but I’ve got an awful lot to live for.”

Here is a man who never saw himself as above others, who saw himself as simply “lucky” for being able to make a modest living doing something he loved. Here is a man, like so many people today, who without warning saw his entire life upended, and yet who had the courage and grace to be thankful for what he had been able to do with his life. Here is a man who humbly accepted the honors bestowed on him throughout his career who saw them as unimportant compared to friendship, family and love. Gehrig’s career was remarkable, yet his outlook on life deserves even more celebration.

No fear of the future

It was therefore inevitable that Hollywood would make a film about Lou Gehrig. Herman Mankiewicz, of Citizen Kane fame, co-wrote the screenplay that was produced, directed, and performed by some of the Studio Era’s most accomplished talents. The film premiered in 1942, just one year after Gehrig’s death, and was nominated for 11 Academy Awards. It remains one of the greatest sports movies ever made, and is certainly a classic of the baseball genre, but it almost didn’t become the film we have today.

Producer Samuel Goldwyn, who had no interest at all in baseball, didn’t want to make the film until he read the account of Gehrig’s closing speech. Immediately, he agreed to make the picture if Gary Cooper played the role of Gehrig. Cooper also had no interest in baseball and was hesitant to make the film since Gehrig’s death was so recent, but a personal visit from Gehrig’s widow Eleanor convinced him to take the role. In truth, only Cooper could have played the part so well.

Cooper had to be instructed in the fundamentals of baseball; special photography and Cooper’s own effort allowed the right handed actor to appear as the left handed Gehrig, but the film is more about a man than it is a game, and the essence of Cooper’s performance is that he seems to fully embody the persona of Gehrig. Even as he is playing a role, he is creating a mythology that remains transcendent today.

Catholics will be interested to know that Cooper was a convert to the faith. Following an audience with Pope Pius XII, Cooper became interested in Catholicism. He began attending Mass with his family and took instructions from a priest. In 1959 he was received into the Roman Catholic Church.

Two years later, Cooper was dead of cancer. Yet much like the man he enshrined in film, he had faith. “I know that what is happening is God’s will. I am not afraid of the future.”

Lou Gehrig and Gary Cooper. How could I not think of them in this historic and frightening moment? When “The Pride of the Yankees” was released in 1942, America was fully engaged in World War II. The movie provided some comfort then, just as it can now.

If you don’t know the film, see it; if you do, see it again. Finally, Richard Sandomir’s 2017 book about the movie that “defined the legacy of Lou Gehrig” provides a fascinating account of ballplayer, actor and film that remain inspiring in troubled times.