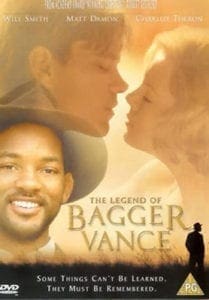

Golf and redemption in ‘The Legend of Bagger Vance’

By DAVID A. KING, PH.D., Commentary | Published June 22, 2018

A constant theme in my many columns for The Georgia Bulletin is tradition, from the Latin tradere, which means literally “to hand one another along.”

A constant theme in my many columns for The Georgia Bulletin is tradition, from the Latin tradere, which means literally “to hand one another along.”

Any parent, any teacher, will tell you that one of the great joys of mentoring is sharing treasured truths, interests and pursuits with those you teach.

So it has come to pass that my sons are now learning to play golf, the game that has brought so much pleasure—and frustration—to their parents over the past 20 years. We didn’t force this interest upon them; they’ve watched us for years, and have decided that now they want to give the game a try, too. Though I wish them better success than I have had, I do hope that regardless of their skill at the game, they learn to honor its traditions and respect its heritage and sense of mystery.

Golf and myth, and golf and faith, have long been, er, linked. A plethora of books—some literary, some instructional, some drivel—has been written about the game, all of which seek to establish a connection between recreation and the meaning of life. Many of them fail, some of them succeed brilliantly, but one golf story that beautifully captures the essence of both the game and its deeper subtexts is “The Legend of Bagger Vance,” which was initially a book by Steven Pressfield and was adapted to the film medium in 2000 by Robert Redford, who whether as an actor or a director has always demonstrated an affinity for the spiritual and mythical qualities of sport.

A sense of the sacred

Pressfield’s book was indebted in many ways to the Hindu text the Bhagavad Gita, so the story itself is infused with a sense of the sacred, but Redford’s adaptation is broader in its spiritual scope. To me, the film best succeeds as a testament to the persistence of mystery, the wonder of the angelic and the blending of the temporal and the spiritual. Above all, the film affirms the possibility of redemption for those who have faith.

Bagger Vance is an angel, and like the best imagined angels, he is an unlikely one. Bagger is a golf caddie, who, like Arthur Miller’s salesman, gets along in life on a smile and a shoeshine. But Bagger is also full of wisdom and love, and he strikes me as the epitome of what we would like our angels to be.

You can’t be a Catholic and not appreciate angels. They are everywhere in Scripture, both the Old and New Testaments, and they serve as both messengers and agents of deliverance who enlighten our understanding of the transient known world by giving us a glimpse of the unseen eternal world.

Because my boys—like almost all Catholic children—learned to recite both the Guardian Angel prayer and the Prayer to St. Michael the Archangel when they were small, they remain enamored with angels. Link that spiritual fascination to a splendid movie about the game they are leaning to play, and you have a wonderful faith lesson for children and adults.

“You lost your swing”

The film is set in Savannah, shortly after the beginning of the Great Depression and over a decade after the return from World War I of the town’s greatest hero, an amateur golf sensation named Rannulph Junuh. While Junuh deals with his lingering post-traumatic stress from the war by drowning himself in whiskey, his former love interest Adele Invergordon is trying to save her dead father’s lavish golf resort from sale and destruction by hosting the greatest golf exhibition match ever played. Adele successfully invites Bobby Jones and Walter Hagen to play in the match, but the Savannah town fathers insist that a local man play in the match as well. At the suggestion of a boy, Hardy Greaves, they try to sway Junuh to play in the match. When Junuh reluctantly agrees, the pieces are set in motion for a story of redemption, reconciliation and instruction in values and virtue.

Junuh, as happens to many people—not just golfers—has “lost his swing.” Though he wants to play in the tournament to reconcile with Adele and honor his home, the war has left him shattered. Then, one evening, as he strikes hooks and slices into the dark of a tidal marsh, Bagger Vance comes out of the night.

Under the pretense of being a drifter seeking only food and shelter for the night, Bagger shrewdly begins dispensing wisdom to the struggling Junuh about the game of golf. “A man’s grip on his club is just like his grip on the world,” he says. “The rhythm of the game is just like the rhythm of life.”

And then he states plaintively: “Well, you lost your swing. We got to go find it. Now, it’s somewhere in the harmony of all that is, all that was, all that will be.”

That gets Junuh’s attention. Wisely, like all the great figures from Scripture who sense when they are in the presence of the angelic, Junuh listens. And with Bagger’s help, everything begins to fall into place.

Bagger’s best speech in the film, given when Junuh is several strokes behind Jones and Hagen, captures the essence of the story: “Inside each and every one of us is one true authentic swing, something we was born with, something that’s ours and ours alone. Something that can’t be taught to you or learned. Something that got to be remembered. Over time, the world can rob us of that swing. It gets buried inside us under all our wouldas and couldas and shouldas. Some folks even forget what their swing was like. But inside every one of us is one true, authentic swing.”

God is always with us

This speech, if not delivered by an actor with the talent of Will Smith, reads like either a well-wrought homily or a motivational talk, and for it to enter the realm of art, it has to be supported by a number of other characteristics, all of which the film contains.

The cinematography is beautiful. Shot in Savannah, South Carolina and Jekyll Island, the movie evokes the crucial qualities of home and place while also endowing them with a sense of mystery. The performances, especially those of Matt Damon and Will Smith, are wonderful. Jones and Hagen seem entirely real. And, in his last film role, Jack Lemmon shines as the film’s narrator, the older—and dying—Hardy.

In many ways, the film is as much Hardy’s story as Junuh’s. In fact, the movie begins with the older Hardy, who suffers his last of many heart attacks while playing golf alone. As he lies, apparently dying, “in the trees with the squirrels again,” Hardy narrates the story of Junuh, Bagger and the golf match. Throughout the film, the young Hardy learns how to couple his love of golf with an understanding of virtue, honesty and integrity. He grows as much as Junuh does, and it’s no coincidence that Bagger tells Hardy, “I’ll be seeing ya.”

Indeed, at the end of the film, in a shot as evocative and moving as the “dance of death” conclusion to Bergman’s “The Seventh Seal,” Bagger appears behind the dunes on the golf course, summoning Hardy to join him and take his place in “The Field.”

The Field is the spiritual center of the game of golf, and life itself. The Field is the outward reflection of the inner soul. Junuh has to learn to find his swing; more importantly, he has to recover his belief in the soul. “Man is alone,” says Junuh, in self-pity. “Ain’t a soul in this world that don’t carry a burden,” Bagger explains.

Speaking of golf, and life, Hagen says “The meaning of it all is that there is no meaning.”

But Bagger knows better. “So, you think a soul is born with everything that the Lord can give it, and things don’t go its way, so it just gives up, and the good Lord takes everything back? No. The soul doesn’t die.”

The golf match makes its way, thrillingly, to an entirely fitting conclusion. Yet all the while, Bagger dispenses as much spiritual wisdom as he does golf instruction. The Field is indeed the heart of the game, but it’s also the heart of the world, and throughout the match, Bagger shows Junuh and Hardy the eternal possibility of both redemption and the miraculous. This insight doesn’t come without suffering; as Bagger wryly observes, “A golf course puts folks through a terrible punishment,” yet Junuh learns well the mystery of redemptive suffering.

Most of all, best of all, the film reminds us that no matter how difficult life may be, God is always with us. “You ain’t alone,” says Bagger. “I’m right here with you. I’ve been with you all along, and it’s time for you to come out of the shadows.”

In one memorable scene, Junuh makes a hole in one; “I’ve just seen a miracle with my own eyes!” Hardy exults. By the end of this simple, transcendent film, however, Hardy will come to understand—as does the viewer with faith—the larger and more enduring miracle that surrounds the life of all of us who seek our place in The Field.

David A. King, Ph.D., is professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and director of RCIA at Holy Spirit Church in Atlanta.