Remembering the heroism of the late Roberto Clemente

By DAVID A. KING, PH.D., Commentary | Published April 19, 2018

“God, I love baseball.”

So says Robert Redford as ballplayer Roy Hobbs in Barry Levinson’s classic film adaptation of Bernard Malamud’s novel, “The Natural.”

If you’ve followed my column for the past several years, you know I love baseball, too, and I frequently write about the game and the many connections it has to Catholicism, culture and spirituality.

Both my boys are active in National Little League, and while they’re both good ballplayers, I am always trying to instill in them a love for the game’s past and its deeper subtexts, particularly the ways in which baseball mirrors our country, our culture and even our faith.

My sons have gotten off to a particularly fine start this year; each has won a game ball for his performance on the field. Just last night, my younger son went three for three and scored the game’s winning run.

My sons have gotten off to a particularly fine start this year; each has won a game ball for his performance on the field. Just last night, my younger son went three for three and scored the game’s winning run.

As I’ve said before in this space, Little League is a beautiful version of the national pastime, but like all levels of baseball, the games can sometimes be slow. When things on the field slow down, I take advantage of the game’s great gift: its invitation for us to pause, to reflect, to observe.

Last night in the aluminum bleachers, with the sun going down behind the oak-lined outfield fence, I looked around at the people intensely engaged by the play of 18 boys, 7 and 8 years old. It was really quite a beautiful tapestry. There were men, women and children of all ages; working-class people in boots and ball caps; commuters with loosened ties, weary from the traffic; and there were black people, and white people, and brown people, and it felt like being at a Mass, anywhere in the world, when the universal Catholic Church is truly one.

And I thought immediately of Roberto Clemente, “The Great One,” who had once said, simply, “I don’t believe in color.”

Sixty-three years ago this week, Roberto Clemente made his Major League debut with the Pittsburgh Pirates, the team for which he would play his entire 18-season career.

Clemente, from Puerto Rico, was the first Latin American man to play Major League baseball, and he was to Hispanic fans what Jackie Robinson represented for black Americans when he broke the color barrier in 1947. Yet Clemente, like Robinson, transcended race and became not only a favorite of all fans past and present, but an enduring symbol of baseball’s reflection of our deepest national values and ideals.

It would be naïve to suggest that baseball never lets us down; the game and its players have failed us many times, especially in the steroid era, but Clemente was different. On the field, and in his life, he epitomized a true and enduring hero.

We’re thinking of baseball, so we have to cite numbers. Consider just these facts: in his 18 seasons, Clemente won 12 Gold Gloves 12 years in a row. He hit over .300 in 13 different seasons. He won two World Series with the Pirates, including the great 1960 series when Bill Mazeroski homered to beat the Yankees in game 7. He was consistently an All Star and an MVP, and in his last at-bat, he became only the 11th man to reach the milestone of 3,000 hits.

He achieved all of this with dignity, grace and style—a style that has often been copied, but which will always be Clemente’s own. Clemente’s approach to the plate was smooth, yet defiant. He dragged his bat, rather than carrying it, almost as though it were a club destined to do his bidding. Always he rubbed his hands in the dirt. And just before assuming his stance, he would wag his head and shoulders, like a cat roused from a nap. Then, usually, and often more than once in a game, he would hit. Clemente was famous for stretching singles into doubles, doubles into triples. His speed served him well in right field, where he made amazing plays with a unique fielding style, almost as if he were gathering peaches in a basket.

“I am convinced that God made me a baseball player,” Clemente said. “I was made to play baseball.”

But Clemente was made for far more than baseball. Throughout his career, every off-season, he devoted himself to charitable causes. “Any time you have an opportunity to make a difference in this world and you don’t, then you are wasting your time on earth,” he said.

A mythic life and legacy

This attitude toward service endeared him to fans, to whom he was ever gracious and grateful, and made him a symbol of selflessness and charity. Sadly, his dedication to the cause of helping others actually cost him his life. On Dec. 31, 1972, while traveling to assist Nicaraguan earthquake victims, Clemente’s plane crashed into the sea. His body has never been found.

His life and legacy, however, have entered the realm of myth. Clemente had a premonition of an early death, and he often made statements such as, “You never know because only God decides how long you’re going to be here,” but in a sense his life endures. Countless awards and honors have been given to him posthumously, and awards in his name are granted to those who follow his example of service to others. One of the most prestigious awards given by Major League Baseball remains the Roberto Clemente Award. Clemente was held in such esteem by the game and the public, that almost immediately after his death baseball waived the customary waiting period and inducted him into the Hall of Fame.

Yet the greatest acknowledgement of Clemente’s legacy may be yet to come. In the past few years, there has been growing support for Clemente’s canonization as a saint.

Filmmaker Richard Rossi, whose recent documentary, “Baseball’s Last Hero: 21 Clemente Stories,” is an excellent chronicle of Clemente’s life, became convinced while making the film that Clemente was not just a good man but an extraordinary example of faith in action. Rossi instituted the petition for Clemente’s canonization and even claims there is proof of at least one miracle associated with Clemente. Most remarkable is the fact that Clemente’s cause for canonization has the formal and public support of Pope Francis. I would not be surprised to see Clemente beatified sooner rather than later.

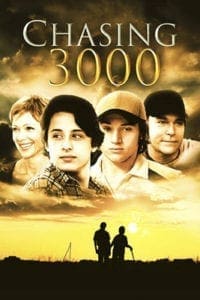

For those interested in developing a further appreciation for Clemente’s influence, I must also recommend—along with the Rossi documentary—Gregory J. Lanesey’s wonderful independent film from 2010, “Chasing 3,000.”

Movie a tribute to baseball hero

“Chasing 3,000” is a classic baseball movie about two brothers, Mickey and Roger Straka (if you don’t get the reference implied by the names, you’re not a baseball fan),

Catholic natives of Pittsburgh who have moved with their mother to southern California. They desperately miss their home, their grandfather, their Pirates and Roberto Clemente. When it becomes apparent that Clemente has an excellent chance to make hit number 3,000 before the end of the 1972 season, older brother Mickey is adamant that he is going to drive cross-country to see the moment in person. They only have a few days to go thousands of miles, and Roger intends to come along. The catch is that Roger has muscular dystrophy. Not only is he in a wheelchair, he’s also sick with a bronchial infection, and when the brothers discover, shortly after they’ve left California, that Roger forgot to bring his medicine, the trip becomes a literal race between life and death.

The movie is a loving tribute to Clemente, and a testament to how much he meant to his fans. At the heart of the film is what constitutes the heart of Clemente himself: do unto others. As Mickey says, baseball is not, after all, about numbers; it’s about heart.

To tell you anymore about the film would spoil not only the plot of the movie, but also the thrilling story of how Clemente reached the 3,000 mark. Even if you’re not a baseball fan, you’ll find the film to be a moving and insightful reflection upon the love of family, a beautiful game, and a very special man who will always be remembered as “The Great One.”

David A. King, Ph.D., is professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and director of RCIA at Holy Spirit Church in Atlanta.