Snow days from a Catholic perspective

By DAVID A. KING, PH.D., Commentary | Published January 25, 2018

In his “Asian Journal,” Thomas Merton wrote, “My dear brothers and sisters, we are already one. But we imagine we are not. And what we have to recover is our original unity. What we have to be, is what we are.”

In “Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander,” Merton acknowledged, “I have no program for this seeing. It is only given. But the gate of heaven is everywhere.”

And in his final talk as novice master at the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky, Merton reflected, “Life is this simple: we are living in a world that is absolutely transparent and the divine is shining through it all the time. This is not just a nice story or a fable, it is true. God manifests himself everywhere, in everything: in people, and in things, and in nature, and in events so that it becomes obvious that He is everywhere and we cannot be without Him.”

I’m thinking about Merton a lot lately, perhaps because this year marks the 50th anniversary of his death. Many people—not just Catholics—will be thinking about Merton’s incredible insights into the human condition and its relationship with the divine throughout the year.

The recent snow days we have had in Georgia have inspired me to retreat into Merton, but I found myself drawn to his work in a roundabout way.

The recent snow days we have had in Georgia have inspired me to retreat into Merton, but I found myself drawn to his work in a roundabout way.

When the wind chill is minus 7 degrees and your furnace breaks down you are forced to wander, stupefied, through your igloo in a military parka, not a cloak of piety!

And yet, by doing what I always do on a snow day, I found myself suddenly in the midst of Merton, and I felt much better.

As T.S. Eliot reminded us in “The Four Quartets,” “We shall not cease from exploration/And the end of all our exploring/Will be to arrive where we started/And know the place for the first time.”

Reminders of what it means to be Catholic

Other than milk, bread, beer and letting the faucets drip overnight, there are a few things that I always associate with a snow day. Most of them are not Catholic. But in contemplating my deep identity as a Catholic, these things actually serve to draw me more fully into my faith, rather than away from it.

Besides listening to a lot of records—snow days particularly make me yearn for folk, jazz and classical music—and watching a couple of favorite films, there are other things I always do in my little house on the tundra.

For one, I avoid going outside as much as possible. If you’re like me, and you grew up in the South before snow days became as commonplace as they seem to be now, you probably recall wearing ziploc bags on your feet before putting on your shoes. The theory was that the bags would keep your feet warm; in truth they turned your feet to popsicles. I have no desire to wear plastic socks ever again.

No, I stay inside on snow days. I don’t shovel. I don’t scrape windshields. And I don’t scrape windshields because I certainly don’t drive on snow days. I read. There are three texts I read every snow day, none of them Catholic, and yet all three bring me to an awareness of who I really am as a Catholic.

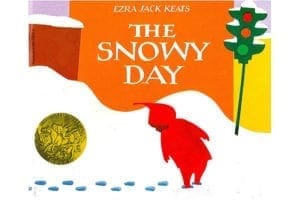

The first text is a picture book, a book that has been called one of the most important children’s books of the 20th century. The book is Ezra Jack Keats’ classic, “The Snowy Day,” which was first published in 1962, and which was an absolute fixture of my childhood. When my oldest son was a baby, and his first snow day loomed, the first thing I did was buy him a hardback edition of a book, complete with dust jacket and Caldecott Medal gold seal.

If you know “The Snowy Day,” you probably are visualizing right now the image of the little boy Peter, the hero of the book, in his bright red snow suit.

Peter is black, and he lives in the city. That may not seem striking to us today, but in 1962, black children and urban environments were not often the subject of mainstream children’s literature. Thankfully, that has changed, and Keats’ book undoubtedly had an enormous influence upon that change.

One might assume, as I did for years before the internet, that Keats was black. He was not. He was a Polish Jew, born and raised in Brooklyn. He was inspired to write the book by a picture he saw in Life magazine, and he was captivated by the image. As he said, “I wanted to convey the joy of being a little boy alive on a certain kind of day—of being for that moment, aware of the things to which all children are so open.”

Keats changed a lot of people’s perceptions through his creation of Peter, and his book reminds me of the fundamental Catholic values of inclusion, unity in diversity and tolerance that are at the heart of our universal church. Looking at the book on a snow day that came so soon after Martin Luther King Day was especially serendipitous.

The second text I always read on a snow day is Jack London’s masterful short story, “To Build a Fire.” The story is about a man and a dog who are in the Yukon during the gold rush, an event London actually participated in. The man and the dog have to get to a lodge before nightfall, and to get there they have to travel on foot many miles through a frozen wilderness in temperatures far below zero—50 degrees below zero to be exact.

London was not a religious man. Beyond subscribing to the literary theory of naturalism—an early modern concept that conceives of human beings as driven neither by purpose nor design but rather by appetites, fate and natural law—London was also an atheist. He said famously, and woefully, that he believed when he died, he would be only one thing: dead—as dead as the last mosquito he squashed.

Obviously, I don’t believe that, but confronting something abhorrent to me actually supports what I do believe. Catholic reason, and the Catholic imagination, liberates us to encounter opposing perspectives not fearfully but gratefully; the thing we cannot understand paradoxically bolsters our faith.

Further, the story is a masterpiece, one of the most compelling studies of mortality I know. Its innate suspense, as well as its eerie inevitability, compels the reader toward a deeper awareness of self and our need for God.

The gift of a priceless memento

The final text that I read every snow day may surprise you, but it will delight those of a certain age who remember, perhaps even with the same legitimate affection and longing that I do, the Atlanta Flames hockey team.

When I was a boy, I absolutely adored the Flames. They were one of the greatest expansion hockey teams of all time, and they represented a completely foreign sport in the Deep South. From 1972-1980, they were a fixture in my childhood. I was in the fan club. I followed games on a portable radio, listening at night under the covers. I had a red Flames jacket, with patches sewn on by my grandmother, and a scrapbook I filled with articles and photos from the AJC and Atlanta magazine. My first real memories of live sporting events are centered upon seats high up in the rafters of the old Omni, screaming for, or at, Pat Quinn, Dan Bouchard, Tom Lysiak, Curt Bennet, Eric Vail and Guy Chouinard. When the team moved to Calgary, in Canada, I wept.

So every winter, and every blessed snow day, I read my copy of Jim Huber and Tom Saladino’s “The Babes of Winter,” the only full-length book ever written about the Atlanta Flames. First published in 1975, and long out of print, the book remains for me a priceless memento from a time long gone in Atlanta history. Reading it transports me back to a time of innocence and joy.

To be Catholic is to know joy, yet it also means finding joy in everything, not just those things that are inherently Catholic.

The day after this article is to appear in The Georgia Bulletin, Sister Helena Burns is coming to my parish, Holy Spirit. She is giving a three-day series of talks over the weekend of Jan. 26-28 on the theology of the body and Catholics and digital media.

Sister Helena is a true “nun on the run”; she has travelled throughout North America and is a sort of celebrity in matters pertaining to contemporary Catholic social thought and culture. When I called her for the first time several weeks ago to confirm her arrangements, I warned her that our telephone conversation might be difficult because of my hearing impairment and the fact that I am a drawling native Georgian and she is a fast talking Canadian.

“Georgia,” she said. “That’s where the Flames came from! Do you like hockey?”

“Yes, sister,” I said. “I do. I do indeed.”

Grace is everywhere. Sister Helena has been sending me hockey scores from Canada, including especially the Calgary Flames. We have much to discuss when she visits. Provided, that is, we don’t have a snow day.

David A. King, Ph.D., is associate professor of English and Film Studies at Kennesaw State University and director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church in Atlanta.