Jewish author presents parables as Jesus’ tales to fellow Jews

By DAVID GIBSON, Catholic News Service | Published August 6, 2015

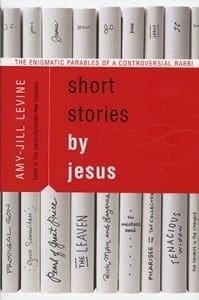

“Short Stories by Jesus: The Enigmatic Parables of a Controversial Rabbi” by Amy-Jill Levine. Harper Collins (New York, 2014). 313 pp., $25.99.

“Short Stories by Jesus,” Amy-Jill Levine’s new book, reaches far back in time to listen “to the Jewish Jesus talking to fellow Jews” as he tells his many parables.

Believers over time domesticated the parables, ridding them considerably of their power to disturb and to surprise, Levine believes. Her goal is to show “what happens when we strip away 2,000 years of usually benevolent and well-intended domestication to hear a parable as a first-century short story spoken by a Jew to other Jews.”

She characterizes this book as “an act of listening anew, of imagining what the parables would have sounded like” to people who had no idea that Jesus would “be proclaimed son of God by millions.”

In a key observation, she concludes that whenever our interpretation of a parable “creates a neat and tidy picture, we need to go back and read it again.” A parable’s interpretation, she asserts, ought to raise questions for us and “open us up to more conversation” about its meaning—its meaning in biblical times and for today.

Levine, the book’s Jewish author, is a professor of New Testament and Jewish studies at Vanderbilt University’s Divinity School and College of Arts and Sciences in Nashville, Tennessee. “The parables,” she writes, “have provided me countless hours of inspiration and conversation.”

A parable is not meant to foster “complacency.” Neither should parables be reduced to “platitudes,” Levine makes clear.

She considers it essential to realize that “parables never go the way one expects.” Instead, they “shake up one’s worldview” and pose questions about what is accepted as “conventional.” It is when a parable “discombobulates us” that “we may be on the right track,” she proposes.

Religion often is said “to comfort the afflicted and to afflict the comfortable,” Levine points out. In this regard, she adds, “we do well to think of the parables of Jesus as doing the afflicting.” Indeed, parables help believers “ask the right questions” about “what ultimately matters” and the kind of life “God wants us to live.”

Levine’s process of “listening anew” to the parables typically means looking differently at a story’s key characters.

It is not unusual today when discussing the prodigal son parable to draw attention to the story’s other, older son, who feels overlooked despite his faithfulness. But Levine rather remarkably brings the older son front and center, while frankly acknowledging her dislike and distrust of the younger, wayward son.

Not to be overlooked, however, is the father’s love for the younger son. Levine notes that the father both loves him and views him as “a member of the family.” So to dismiss the younger son would be to “dismiss the father as well,” she writes.

Nonetheless, what the father in this parable discovers is “that the elder was the son who was truly ‘lost’ to him.” Having realized this, the father sought “to make his family whole.” He endeavored to show that “were either brother to be missing, the family would not be whole.”

The parable of the prodigal son provokes people today “with simple exhortations,” Levine writes. It provokes readers, for example, to “recognize that the one you have lost may be right in your own household.”

It takes work to find “the lost,” she says, but “from those efforts there is the potential for wholeness and joy.”

Levine’s analysis of other parables is similarly thought provoking. I particularly welcomed her explorations of the parable of the good Samaritan and of the rich man and Lazarus. Conventional understandings of these parables often reflect basic misunderstandings of the culture and Judaism of Jesus’ time, she indicates.

She notably points out that St. Luke’s Gospel (Chapter 16, verses 19-31) makes Lazarus, the poor man lying at a rich man’s gate, known by name to readers. He is not “just ‘some guy’; he is Lazarus,” even though “in parables, characters are rarely named.”

Levine writes, “That Jesus proclaimed the poor blessed finds enactment in this parable.”

She notes that the parable’s original Jewish listeners would have viewed the rich man as someone who “placed himself outside the system” because he failed “to extend his hand to the poor and instead” lived “an epicurean life” unmarked by generosity.

A particular concern for Levine is the way parables often are used to play Christians off against Jews. She writes: “When Jewish practice or Jewish society becomes the negative foil to Jesus or the church, we do well to reread the parable.”

Levine hopes Jews and Christians today will “find some common bonds or at least common challenges” in “Short Stories by Jesus.”

I can well imagine the book as a resource for discussion by Catholic-Jewish dialogue groups in dioceses, parishes, universities and other settings. Many others, too, will find it valuable for exploring the deep roots of faith that Jews and Christians share.

Gibson was the founding editor of Origins, Catholic News Service’s documentary service. He retired in 2007 after holding that post for 36 years.