‘The Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes’ a highlight of Tissot’s Life of Christ series

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D. | Published August 8, 2024

My favorite miracle story in the New Testament has always been the Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes, or as it is also known, “The Feeding of the Five Thousand” or “The Feeding of the Multitude.” We read the story in the liturgy just a couple of weeks ago, so it’s been on my mind.

The miracle is the only one that appears in all four Gospel accounts, and St. Mark’s Gospel even includes two versions of it. The event has profound significance for Catholics, as it is considered one of the eucharistic miracles that underscores both the Real Presence and the boundless grace associated with the sacrament. Tellingly, the story appears in Chapter 6 of St. John’s Gospel, immediately before Christ walks on the water and the famous Bread of Life discourse.

Like most familiar stories in the Gospels, the Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes has been adapted into film and literature, and it has always been especially retold for children. It has been rendered in countless illustrations and paintings. Yet to me, there is perhaps no more revealing depiction of the miracle than in James Tissot’s small painting that is one of the hundreds of watercolors in his famous Life of Christ series.

At one time, Tissot’s paintings and illustrations were recognizable to audiences worldwide, and they were featured in numerous editions of the Bible. In the digital age, Tissot’s work remains relevant, and his artwork complements numerous Catholic websites and blogs.

Jacques Joseph Tissot was born in France in 1836. From a young age he knew that he wanted to be a painter, and he studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. By his early 20s, he was exhibiting in the Paris Salon. Tissot had a versatile style and worked in a variety of media. He was drawn to medievalism, but also to English Victorianism, and he was as comfortable painting highbrow subjects as he was magazine illustrations and cartoons. He knew and worked with the early Impressionists, including Manet and Degas. Tissot was particularly fond of painting fashionable and beautiful women in lavish settings; looking at these paintings today, many of them seem cluttered and overwrought, the product of a distinct time and place that the pictures sometimes fail to transcend.

Tissot was a dashing man, drawn to adventure and travel, and he served in the Franco-Prussian War. Though he was clearly fascinated by romance and high society, he had one great love, an Irish woman named Kathleen Newton, with whom he had a passionate relationship for about seven years. Newton contracted tuberculosis in 1880; two years later, she died in Tissot’s arms.

Not long after Newton’s death, Tissot’s life changed dramatically. Up to this point, he had lived much like Augustine or Thomas Merton—clearly gifted and called to a purpose but unwilling to commit. Tissot had always practiced, even if loosely, his Catholic faith; indeed, he never married Kathleen Newton because she had been divorced from her first marriage. But his fascination with the material world had a strong hold on him.

A transformation of vocation

In 1885, while attending Mass at the Church of St. Sulpice, Tissot experienced a profound vision. As the priest elevated the host, Tissot claimed to have seen a bloodied and tormented Christ, much like he later depicted in his painting “Ecce Homo,” in which Pilate presents Jesus to the mob. The experience immediately transformed his life and his vocation, and he dedicated his painting to a deep exploration of Christianity.

Beginning in 1886, and in subsequent journeys, Tissot travelled to the Middle East where he immersed himself in a study of the Holy Land—culture, customs, topography and people. He transferred his meticulous notes and observations into a massive series of watercolors, painted in gouache, that depict scenes from the entirety of Christ’s life. The entire series, which took about 10 years to complete, contains more than 350 finished paintings, with even more sketches and studies. Of the intensely disciplined schedule he set for himself, and the challenge of the opaque watercolor technique, Tissot echoed the Benedictine Rule when he said his work “was not a task; it was a prayer.”

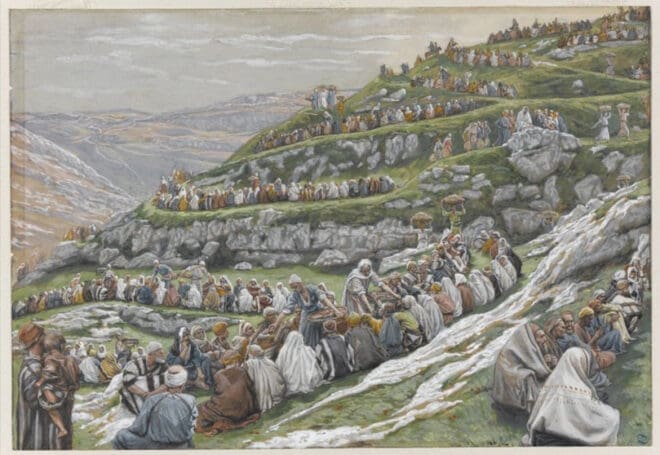

“The Miracle of the Fishes and the Loaves” by James Tissot is part of the Brooklyn Museum’s European Art Collection. -Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The entire series of paintings is staggering in its variety. Many of the pictures have a mystical quality so that some even seem to shimmer. Some of the most interesting are those drawn from imagination rather than Scripture. Most of the watercolors prominently depict Christ, but some of the more effective paintings don’t feature Jesus at all. “Saint Joseph Seeks Lodging in Bethlehem,” for example, is especially evocative.

In truth, many of the paintings must be taken in context with the whole, though there are a few that are striking works on their own. “The Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes” is such a painting.

Tissot seemed to be more interested in capturing historical authenticity than stirring emotion or devotion. Many of the paintings, therefore, don’t seem traditionally religious, though this quality keeps most of the pictures from becoming sentimental. Yet the Loaves and Fishes painting strikes me as deeply spiritual.

Discovering Christ

In the painting, Jesus is almost indiscernible. He could be anyone in the massive crowd that Tissot depicts. As the viewer scans the image, however, Christ appears in the upper right background. Rather, he seems revealed. The effect of spotting him is much like discovering a word in a puzzle, or an image in a “spot-the-difference” exercise. It is an effect like that achieved by Breughel in his “Landscape with Fall of Icarus,” in which the key figure in the massive canvas is reduced to two legs sticking out of the sea.

Tissot’s depiction of Jesus is a literal visual translation of “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us.” This is further amplified by the fact that the heavens and the earth are literally touching each other. This quality is then echoed by the association of the people with the land. The painting therefore emphasizes integration, not juxtapositions. Heaven and earth, land and person and God and man are all one.

Tissot organizes the hillside on which the people recline to eat as a clearly terraced slope. In fact, it’s easy to discern seven distinct levels, much like Dante’s vision of Purgatory as a seven-story mountain. A closer look at Jesus reveals him blessing the loaves and fishes at what clearly represents an altar, but which more tellingly appears to foreshadow his tomb. While only a few figures in the foreground are in focus, the people on both left and right are very interesting. In the left corner, a man stands holding a small child. The gaze of each is in perfect alignment with the figure of Christ. On the right side, we see the faces of some old men and a hooded figure whose gender is concealed. The men seem to be astonished. The overall effect of the young and old, the seen and unseen, is one of wonder.

In its simplicity, this little painting belies great complexity and effort, particularly considering that it was painted in watercolor. Yet as admirable as the details are, the real artistic accomplishment is the unity of effect. The viewer considers the image and thinks, yes, that must have been exactly what it looked like.

I particularly like the child’s perspective that drives the whole painting from the lower left to Christ in the upper right. The picture compels us to look at the episode from the innocent point of view of a child, exactly as Jesus instructed us to do.

Tissot’s Life of Christ series was an instant success when the watercolors were first exhibited in 1894. The Brooklyn Museum in New York purchased the paintings in 1900, two years before Tissot died. The paintings were the focus of a large exhibition at the museum in 2010, and a catalog of 350 works was published in connection with the show. Additionally, the paintings can be viewed in online galleries and other websites devoted to Tissot’s work.

David A. King, Ph.D., is professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and director of OCIA at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.