‘Guadalcanal Diary’ and Father Francis W. Kelly

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D. | Published May 1, 2023

As Paul Simon sings on the great album “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” “I never got the chance to serve; I did not serve.”

I’m told I had a great-grandfather far removed who served in the American Revolution and had a not-so-distant relative who was a Seabee in World War II. My father, however—drafted and even given a physical for Vietnam—got a deferment from that conflict because of me, a high-risk pregnancy. He thanked me his whole life for saving him from that war.

No, as a proud member of Generation X, I never saw combat. My whole adult life, from adolescence to middle age, was marked not by participation in military action, but instead by terrible disease, from the AIDS epidemic to the COVID-19 global pandemic. My only experience of war as a young man was the beginning of the 1990 Gulf War, which unfolded like a video game on CNN.

And yet, as the father of two young sons growing up in a troubled and conflicted world, the threat of another global conflict is one of my greatest anxieties. I worry about Ukraine and Russia and that war’s implications for Europe. I am anxious about China and Taiwan. I am horrified by the fighting in Sudan. St. Padre Pio, my patron saint, says “Pray, Hope, and Don’t Worry,” so I pray my boys never have to face the horror of war.

If they ever do, I hope they can rely on the aid and comfort of a military chaplain like Father Francis W. Kelly, who is a key figure in the various narratives of the World War II campaign for Guadalcanal, which ended 80 years ago.

The campaign for Guadalcanal, an island in the Solomons upon which the Japanese wanted to construct a strategic airfield, was one of the most important engagements in the Pacific Theater of the war. The battle was fought for six months between August 1942 and February 1943. U.S. Marines, supported by Naval forces and later the U.S. Army, defeated the Japanese in a bloody and prolonged struggle marked by both guerilla jungle warfare and relentless air and naval attacks.

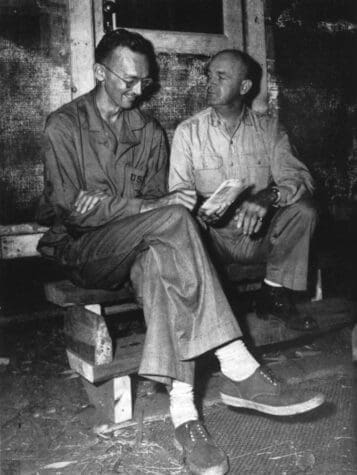

An official U.S. Marine Corps photo of Richard Tregaskis, left, with Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift. Tregaskis was embedded with the Marines in Guadalcanal. General Vandegrift commanded the 1st Marine Division there.

In 1942 journalist Richard Tregaskis, a pioneer of what would become the “New Journalism,” was embedded with U.S. Marines in their initial assault and occupation of Guadalcanal. His book, “Guadalcanal Diary,” remains a classic of combat reporting.

Tregaskis’ book was adapted into a brilliantly edited and acted film in 1943 by 20th Century Fox. Lewis Seiler directed a stellar cast of actors who comprised the typical combat film genre “Squad” of characters—the immigrant American (Anthony Quinn); the naïve country boy (Richard Jaeckel); the Brooklyn stalwart (William Bendix); the loyal officer (Richard Conte); the gruff sergeant (Lloyd Nolan); and the Catholic Chaplain, or “Padre” (Preston Foster).

Foster’s character—Father Donnelly—is based upon the real Naval Chaplain Father Francis W. Kelly, a Catholic priest from Philadelphia. Father Kelly had a stellar career as a military chaplain. He won the Legion of Merit and Purple Heart.

In addition to his service on Guadalcanal, Father Kelly served with Marines in the fierce battles of Tarawa and Okinawa, even suffering combat wounds on Tarawa. His Legion of Merit citation for Tarawa cited his “exceptionally meritorious conduct in tirelessly helping the wounded and comforting dying men in the last moments.”

Father of the foxhole

He went on to serve as well in the Korean War. The Marines gave him the nickname of “Father Foxhole” because he never hesitated to be with infantry in the most dangerous of situations—a quality beautifully presented in the film version of Guadalcanal Diary. He later rose to the rank of Monsignor and was buried in Arlington Cemetery following his death in 1982.

Tregaskis’ book opens with a direct reference to Father Kelly: “Father Francis W. Kelly of Philadelphia, a genial smiling fellow with a faculty for plain talk, gave the sermon. It was his second for the day. He had just finished the ‘first shift,’ which was for Catholics. This one was for Protestants. … The sermon dealt with duty, and was obviously pointed toward our coming landing somewhere in Japanese-held territory. Father Kelly, who had been a preacher in a Pennsylvania mining town and had a direct, simple way of speaking which was about right for the crowd of variously uniformed sailors and marines standing before him, pounded home the point.”

Father Kelly appears several times in Tregaskis’ book, and he becomes a central character—perhaps the most important—in the film under his cinematic name Father Donnelly.

The character of the Catholic priest is prevalent in Studio-Era Hollywood, and he appears in many films as a benevolent, wise, and confident figure. These qualities are certainly evident in Father Donnelly’s character. The priest never picks up a weapon, but with his faith and quiet strength, he fights as hard as any of the Marines.

Even before the landing, in addition to celebrating Mass and leading ecumenical services, he is happy to join in the joking and mischief that alleviates the anxiety of the coming combat.

Following a surprisingly uncontested arrival on the island, Father Donnelly aids the Marines in discovering Japanese contraband and then administers Last Rites to the first casualty.

He selflessly volunteers to go forward into action with the troops, saying that he will be most needed then, and after a series of firefights, he serves the wounded in the field hospital, comforting their suffering with a quiet patience.

He attends surgery, even during an air raid, in case he is needed to administer sacraments.

In the film’s most powerful scene during a terrible naval and aerial bombardment, Father Donnelly huddles in a foxhole with terrified men—some sobbing, some praying—and listens with empathy and understanding to the pleas and laments of men of many different faiths. This is one of the most compelling moments in the film, with improvised acting by both William Bendix and Preston Foster. It reminds us that when the movie was made, the war was not even halfway through, and the battle for Guadalcanal had only recently ended.

Before the climactic enormous battle for the airstrip that became Henderson Field, the priest hears countless confessions. Framed in the background, Father Donnelly sits as man after man approaches him, face-to-face, to make peace with God. Each soldier is given an encouraging laying on of hands by the priest.

Following that battle, a successful but costly victory for the Marines, Father Donnelly conducts funeral services in which he calls the dead by name. Refusing to accept them as mere statistics in combat, he names them by the nicknames their friends and comrades in arms called them.

By all accounts, Preston Foster’s Father Donnelly is an accurate and touching portrayal of a real man—Father Kelly—who gave profoundly of himself in service to his country and to the ordinary boys and men who gave so much in defense of our greatest national values.

I once wrote a poem about riding in a troop transport with my boys, then small, at a neighborhood block party. I concluded the poem with a prayer that if my boys ever had to ride in such a transport in the conditions for which it was intended, that I could be at their side. I know that’s not possible. But I remain grateful for the Catholic military chaplains like Father Kelly, who have always been there, and who will always be, so that we can indeed “let not our hearts be troubled or afraid.”

David A. King, Ph.D., is professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and director of RCIA at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.