The Library Card episode in Richard Wright’s ‘Black Boy’

By DAVID A. KING, Ph.D. | Published March 19, 2021

I’m writing this column on March 11, a year to the day when the COVID-19 global pandemic changed everything. We have all suffered through this year, and millions continue to suffer. Beyond the terrible loss of life and livelihood there is also another difficult loss—the loss of simple, ordinary pleasures that we once took for granted.

I’ve not been in a restaurant or bar for more than a year. I haven’t been in my favorite record store because it’s too cramped. I don’t remember the last time I went to the movies. I haven’t been to the public library, a place I’ve gone to at least once a week for almost my entire life.

Blessedly, I have been able to read even though libraries, like so many other ordinary places, have been closed throughout the pandemic. In Cobb County, as throughout Metro Atlanta, libraries have offered online borrowing with curbside pickup. When books are returned, they—like people—go into quarantine.

I never imagined I would be denied the small joy of the public library, especially in March, which is National Reading Month.

The great writer Richard Wright almost never had that joy at all. Growing up Black in the segregated Jim Crow South, the public library was closed to him. A trip to the library for Richard Wright was like a secret mission, the failure of which could literally jeopardize his life.

The power of knowledge

A famous episode from Wright’s autobiography, “Black Boy,” makes painfully vivid not only the consequence of being denied the ability to read, but also demonstrates the transformative power of language and knowledge.

The scene is typically titled “The Library Card;” it is easy to find online, and William Miller, a renowned writer of children’s books on Black history, has written a beautiful illustrated adaptation for young readers.

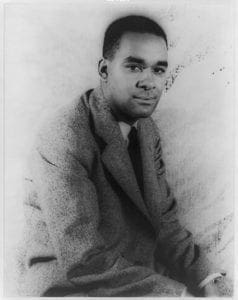

Richard Wright, author of short stories and novels, is seen in this 1939 photo. His memoir, “Black Boy,” was published in 1945. Photo from Carl Van Vechten Photographs Collection, Library of Congress

Yet Wright’s book, and Miller’s adaptation, both transcend Black history and experience. “The Library Card” episode is a testament to the universal cruelty of ignorance and the possibility for redemption, as well as a denunciation of prejudice and hate and a reminder of our shared responsibility to our neighbor.

The story is simple. One day, Wright arrives at work at a Memphis optical company. Several of the men are arguing about an article by H.L. Mencken that had been syndicated in the local paper. Mencken was infamous for writing inflammatory opinion pieces about the South, and apparently his most recent column had really angered the white men on the job. Wright is curious; “I wondered what on earth this Mencken had done to call down upon him the scorn of the South.” Naturally, he wishes he could read some of Mencken’s work, but he can’t. “There was a huge library near the riverfront, but I knew that Negroes were not allowed to patronize its shelves any more than they were the parks and playgrounds of the city.”

Wright tries to figure out a way that he can get books from the library. He considers all the different men on the job, and sadly realizes that none of them will help him. And then he remembers one possibility: “There remained only one man whose attitude did not fit into an anti-Negro category, for I had heard the white men refer to him as a ‘Pope lover.’ He was an Irish Catholic and was hated by the white southerners.”

The Catholic’s name is Mr. Falk, and when Wright asks him to help get books from the library, he agrees. “It’s good of you to want to read,” he says. “Let me think. I’ll figure out something.”

Mr. Falk loans Wright his library card, but in order to use it, Wright must forge demeaning notes that make it appear he is simply running errands for Mr. Falk. The librarian is suspicious, but she relents, and over time it becomes easier for Wright to borrow books under this scheme.

Throughout the episode, Mr. Falk is the only one who encourages Wright in his reading. The other characters mock and chide him; they seem to doubt that Wright is incapable of thinking, let alone reading.

Yet read he does, and as he reads alone in his room at night, Wright is struck by a revelation. It is a revelation that most avid readers remember from their own experience: “What strange world was this? I concluded the book with the conviction that I had somehow overlooked something terribly important in life. … I hungered for books, new ways of looking and seeing. It was not a matter of believing or disbelieving what I read, but of feeling something new, of being affected by something that made the look of the world different.”

As time goes by, Wright literally educates himself through his secretive errands to the library. He reads modern literature especially, for as he realizes “All my life had shaped me for the realism, the naturalism of the modern novel, and I could not read enough of them.”

As he continues his reading, Wright at last has a tragic epiphany: “I now knew what being a Negro meant. I could endure the hunger and I had learned to live with hate. But to feel that there were feelings denied me, that the very breath of life itself was beyond my reach, that more than anything else hurt, wounded me. I had a new hunger. In buoying me up, reading also cast me down, made me see what was possible, what I had missed.”

Yet Wright reads on, quietly assisted by the loan of Mr. Falk’s library card; the two men never speak of Wright’s reading.

Mr. Falk’s simple gesture of aid, along with Richard Wright’s innate genius, created one of the most remarkable literary voices in 20th century American literature. Wright’s novel “Native Son,” his wonderful short stories, and his autobiography are all masterworks of modern fiction and memoir.

A change in perspective

I read “Black Boy” in a 10th grade honors English class, and the book instantly changed my perspective of life. Even now, when asked to name the books that most influenced me, I list “Black Boy” among my selections. Until I read Wright’s book, I had never confronted the issues of race and poverty, and I had never really been challenged to think outside my own limited experience. The thought of not being able to use a library card to borrow books from a beloved public institution shocked me then, and shocks me now. Anyone fortunate enough to be a student should be required to read at least “The Library Card” episode; it’s one of the first texts my world literature students encounter.

“Black Boy” was published in 1945 and was a main selection of the powerful Book of the Month Club, which insisted on expunging almost half the book before publication. For three decades, the second half of the book, which takes place in Chicago after Wright leaves the South, had not been published as a complete work. In 1991, an unabridged version was finally published, but for years the slim paperback that I had read was the edition known by most readers.

Throughout my work for The Georgia Bulletin during this pandemic year, I have tried to focus on the small, good things that have come from this experience. I have also remained committed to the ideal that art and language and narrative have the transcendent ability to empower change. To deny anyone this revelation is a terrible injustice. Richard Wright’s “Black Boy” is a powerful reminder of our ability to use both simple benevolence and self-education to bring goodness to the world, and it remains a relevant and empathetic book, particularly useful in a time of suffering.

David A. King, Ph.D., is professor of English and film studies at Kennesaw State University and director of RCIA at Holy Spirit Church, Atlanta.