Photo By Michael Alexander

Photo By Michael AlexanderAtlanta

Photo inspires look back at era when Catholic schools desegregated

By GRETCHEN KEISER, Staff Writer | Published January 9, 2014

ATLANTA—Fifty years ago, federal court pressure was forcing Atlanta to dismantle an unjust segregated public school system.

The bishops of Georgia and South Carolina decided that this was the right time to also desegregate the Catholic schools.

Documents in the Archdiocese of Atlanta Archives show what a stressful and carefully planned effort this was over several years.

The bishops in Atlanta, Savannah, and Charleston, S.C., struggled initially to agree on how to approach informing their people. The three decided to issue not a statement, but a pastoral letter, which was read to local Catholics on the first Sunday of Lent 1961. It set—in a moral framework—their decision to admit Catholic students, regardless of their race, to all the Catholic schools “as soon as this can be done with safety to the children and the schools.”

Until then, blacks—Catholic and non-Catholic—could only attend Catholic schools set up to educate black pupils. In Atlanta, those were two elementary schools, Our Lady of Lourdes in the Old Fourth Ward, established by the Blessed Sacrament Sisters and priests of the Society of African Missions, and St. Paul of the Cross, a Passionist-run parish and school in northwest Atlanta. Drexel High School, built for black students, had just begun in 1961.

While the bishops did not select a date for Catholic school desegregation, they established a common course, saying, “certainly this will be done not later than the public schools are opened to all pupils.” They also set a “program of preparation” in motion during 1961.

“Pastoral letters, sermons, student clubs and school instruction will explain the full Catholic teaching on racial justice,” the bishops’ letter said.

“This affirmation for our diocese is not just a minimum approach to full Christian justice. In a region where our Catholic population is less than 2 percent, it is an honest effort to influence a way of life that has prevailed for many decades,” the bishops said. “Millions of people have accepted this way of life in good faith. Now, both whites and Negroes face a tremendous challenge—to live in a community with full Christian justice for both.”

The bishops were Bishop Francis E. Hyland of Atlanta, Bishop Thomas J. McDonough of Savannah, and Charleston Bishop Paul J. Hallinan.

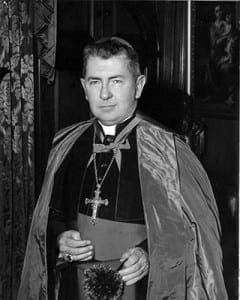

What Bishop Hyland began in Atlanta regarding school integration, Bishop Hallinan would implement. In 1962, Bishop Hyland retired and Archbishop Hallinan succeeded him and became archbishop of Atlanta.

Holy Spirit won’t ‘let down three of his men’

Archbishop Paul J. Hallinan

The process of desegregation, mandated by the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 decision that separate schools based on race were inherently unequal, had not come quickly either to public or parochial schools. Riots occurred in Little Rock, Ark. Schools in Virginia were closed initially when ordered to desegregate.

According to the Southern Education Reporting Service (SERS), it was not until 1960 that the public schools in the South opened without violence.

Catholic schools in North Carolina, Virginia and Louisiana had desegregated by 1961, but those in Alabama and Mississippi had not, except at some Catholic colleges.

A federal court ordered the Atlanta public schools to begin desegregating in September 1961 and nine black pupils entered four high schools. All other Georgia public schools were still segregated.

The University of Georgia had been integrated under court order in January 1961 by two students, Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes, a turning point that led initially to a campus riot. Georgia Tech voluntarily admitted three black students in the fall of 1961, according to SERS.

According to the archives, in October 1957 Bishop Hyland had asked his “consultors”—a small group of chosen priest advisors each bishop has—about integrating Atlanta’s new St. Pius X High School, opening in 1958, because there were 87 black Catholic students who were ready for high school.

However, a majority of the consultors said, “integration at this time because of the political climate would be imprudent.” They feared punitive measures from the state of Georgia—perhaps a change in the Catholic school’s tax status or a loss of teachers’ licenses for religious.

Bishop Francis E. Hyland

Four years later, Bishop Hyland wrote of his confidence in the three bishops now acting to desegregate the schools together.

In a January 1961 letter to Bishop Hallinan, he said, “I agree that it is time for us to speak up, and, acting in concert, gives us a strength which none of us possesses alone. Following your own prayerful example, I resolved to offer Holy Mass every other day for the spiritual success of our venture. Personally I do not think the reaction will be an unfavorable one on the part of some as we may fear. I am inclined to think that a substantial number of people in the South want this issue settled justly as well as peacefully.”

He recommended that the pastoral letter say something to allay fear.

“Fear seems to me to be uppermost in the mind of most Southern people in relation to segregation … fear of the changes, particularly social changes, which integration may eventually entail,” Bishop Hyland wrote.

In a daily diary he kept, now in the archdiocesan Archives as part of the Cardinal Joseph L. Bernardin collection of Archbishop Hallinan material, Bishop Hallinan expressed his own struggles to push through uncertainty about the timing and to trust in God.

“Dear God, thanks for your steady help. Please keep it up,” he wrote on Jan. 15, 1961, a month before the pastoral letter was published. The night before he said he had “temptations … to postpone the Pastoral Letter … but it’s all clearer in the morning. Pray for strength and courage and … guidance.”

On Feb. 7, 1961, he wrote to Bishop Hyland, “I have put away all doubts. The Holy Spirit is not going to let down three of his men.”

Bishops’ letters ‘more than mere straws in the wind’

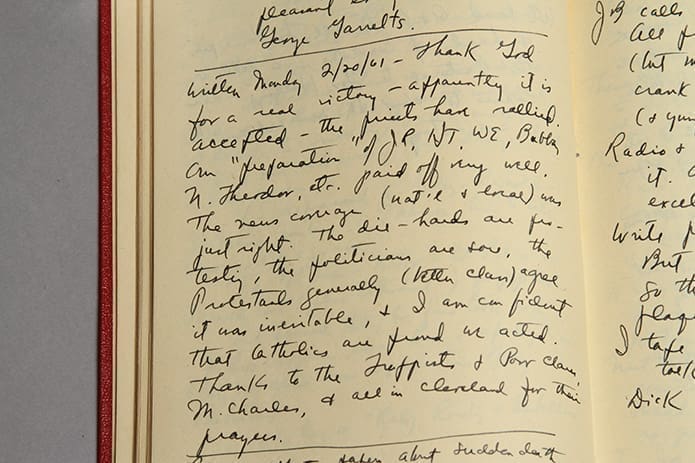

The pastoral letter was read on Feb. 19, 1961, and Bishop Hallinan wrote the next day, “Thank God for a real victory—apparently it is accepted. The priests have rallied. … The news coverage (national and local) was just right. The die-hards are protesting. The politicians are sore, the Protestants generally agree … it was inevitable and I am confident that Catholics are proud we acted.”

According to an Atlanta Journal article, there were 270 black children in the two black elementary schools of the Atlanta Archdiocese and 6,452 white children in 17 elementary schools and two high schools. Black children made up only around 4 percent of the students.

Atlanta Constitution editor and publisher Ralph McGill wrote in his column on Feb. 26, 1961, “These three pastoral decisions, in two deep-South states, are important. They already have caused considerable soul-searching in Protestant churches which operate or control private or parochial schools.”

“Change is coming,” McGill continued. “If intelligently met and understood, it need not bring any shock or great difficulty. It is only when there is long defiance of law and of court orders that violence and grief come.”

“The bishops’ letters are more than mere straws in the wind,” he wrote. “They say what many a silent Protestant minister would like to tell his congregation if he had apostolic authority behind him.”

But announcing the intention to desegregate the Catholic schools was only one step. Setting the date for the actual integration of the schools took more time. The integration was finally set for September 1962.

Archbishop Hallinan, who had been installed in the Atlanta Archdiocese in April 1962, was the bishop who brought integration about.

He wrote a four-sentence draft statement announcing school integration in his diary on April 10, 1962. The day’s notes end with, “I pray over (integration) problem—hope it can be done.”

He met May 7 with former Atlanta Mayor William B. Hartsfield, “a fine conference.”

“He advises letting more lay people in on it,” so the archbishop began to add racial integration into his comments in meetings with parishioners.

By May 15, he had spoken to Atlanta’s Mayor Ivan Allen, the city’s police chief, Herbert Jenkins, the priests of the archdiocese and laymen, telling them that the 1961 pastoral letter would be put into action.

“I have been both surprised and pleased to find a general agreement that the Church should move soon, that although there would be some opposition, the general reaction could be rated as favorable to neutral,” Archbishop Hallinan wrote to Marist Father Vincent Brennan.

He said six black students had already applied to archdiocesan high schools.

The consultors formally approved the school policy change on May 24, 1962.

A second pastoral letter went out on Pentecost Sunday, June 10, 1962, informing Catholics that “Catholic children, regardless of race or color, will be admitted to Catholic schools of the Archdiocese as of Sept. 1, 1962.”

“This decision, promised in the Pastoral Letter of 1961, has been made after long and prayerful deliberation, and has been unanimously approved by the members of the Archdiocesan Board of Consultors and the superiors of religious institutes,” Archbishop Hallinan wrote.

A press conference held that morning included the New York Times and national wire services. Charlayne Hunter came as a reporter.

17 children are ‘pioneers’ in desegregation

Although the decision was announced in June, archdiocesan high schools had already started interviewing and considering eighth-graders who wanted to go to Catholic high school in April, implementing the integrated policy. The elementary schools took new registrations until July 15, 1962.

At the end of the summer, 17 black pupils were registered to enter previously all-white Catholic elementary and high schools in the Atlanta Archdiocese.

Seven went to St. Joseph’s High School, located on Courtland Street in Atlanta. One entered Marist School, Atlanta. Among the elementary schools, three each went to St. Joseph School, Marietta, and St. Joseph School, Athens, while two entered Immaculate Conception School, Atlanta, and one, St. John the Evangelist, Hapeville.

The number of blacks who wanted to register in previously all-white Catholic schools was “very light,” Archbishop Hallinan acknowledged in a letter to the pastor of Immaculate Conception Shrine.

A few were kindergarten or first-graders whose parents wanted them to enter the black schools of Lourdes or St. Paul of the Cross, but could not get them in because those schools were full.

Archbishop Hallinan wrote letters to each of the families, telling them they and their children, whom he called “pioneers,” “will merit a great share of the credit and good will that will come to our beloved Church as this new program goes into action in September.”

“Your family will be constantly in my prayers and Mass during these days,” he wrote.

In a letter to the Atlanta police chief, the archbishop said, “Thus far, there has been no appearance of trouble or disturbance. However, these things can start spontaneously and irrationally, and we are grateful for the assurance of police protection.”

Jenkins had offered to have each of the newly integrated schools quietly patrolled, to respond to bomb threats, and “if feasible,” to have black policeman in plainclothes “accompany the children the first days of school.”

Archbishop Hallinan decided to release no information until the afternoon of the first day of school and then only to name the schools.

On Sept. 4, 1962, the 17 children integrated the Catholic schools in the Atlanta Archdiocese without incident.

Catholic schools in the Savannah Diocese were integrated a year later in September 1963.