Detective fiction and the religious imagination

By DAVID A. KING, PH.D., Commentary | Published February 22, 2018

For many of us, last Wednesday represented a once-in-a-lifetime event: as you must be aware, Ash Wednesday and Valentine’s Day fell on the same day, the first time such a convergence has happened since 1945.

I haven’t been as confused since last year’s total eclipse.

The Sunday before, our pastor joked that instead of the traditional Valentine’s Day steak dinner, we could all have lobster instead. But, of course, as he reminded us, that would be missing the point.

I confess it was difficult indeed to reconcile the beginning of the penitential season of Lent with what has become a secular feast, a day which seems to grow more bombastic and expensive with each passing year.

We managed to observe both days, though the avoidance of snacking between small meals was no easy trick considering the abundance of chocolate my boys brought home from school.

Valentine’s Day and Ash Wednesday are certainly both about love. The former calls us to celebrate the gift of earthly love, whether romantic or familial, while the latter serves as an invitation to return wholeheartedly to the love and friendship of God. Still, it’s not easy to correlate the festive with a day that acknowledges sin and our need for lamentation and penance.

We may have been told to repent from sin and believe in the Gospel; we might have been reminded that we are dust and unto dust we will return, but regardless of the gentle admonishment, it was tempting to see the day as a struggle between the proverbial angel on one shoulder and devil on the other.

The conflict at the heart of detective fiction

Many people believe that as human beings we possess both a good side and a bad side. The Catholic, however, understands human nature as singular. We have the ability to do good, and the capacity to commit evil, yet these faculties aren’t separate; they combine within us so that we can more fully comprehend our place in salvation history.

Many people believe that as human beings we possess both a good side and a bad side. The Catholic, however, understands human nature as singular. We have the ability to do good, and the capacity to commit evil, yet these faculties aren’t separate; they combine within us so that we can more fully comprehend our place in salvation history.

The conflict between abstinence and indulgence that played out for us last Wednesday is at the heart of classic detective fiction; indeed it might be said to be the defining characteristic of both the design of the murder mystery and the pleasure that many of us take in reading and watching such stories. One of the great moral delights of the mystery is that while the reader knows he would never actually commit the crime, he can derive pleasure from reading about it. Further, the reader is granted the moral satisfaction of seeing the guilty revealed, apprehended and punished.

In short, the classic mystery satisfies our need for both pleasure and moral justice.

Religion, and particularly a religious tradition that is saturated with ritual and symbolism, serves much the same aim. We delight in the liturgy, the sensory pleasure associated with “smells and bells,” the comfort of the familiar, and at the same time we are reminded to follow the leanings of the better aspect of our nature. Though detective fiction cannot supply us with genuine grace—only the sacraments can do that—it does in fact echo in many ways the means by which we are spiritually nourished in the church.

It should be no surprise, therefore, to recall that many of our greatest mystery writers had or have deep religious convictions. Nor should it surprise us that many of our most beloved sleuths are often associated with the clergy, whether Catholic or Anglican.

In fact, a Catholic priest, Msgr. Ronald A. Knox, was actually a founding member of the English Detection Club. In addition to writing mysteries himself, Msgr. Knox also compiled “The 10 Commandments for Detective Novelists” in 1928, which established guidelines for the genre that are still widely observed today.

Coverage of the history of the detective novel is beyond the scope of this essay; suffice it to say that a number of important writers—among them Edgar Allan Poe, Arthur Conan Doyle, Dorothy Sayers, and even Charles Dickens—all helped develop the genre. Poe and Doyle are most important, and to this day debate rages between Britain and the United States as to who better deserves the title of father of the detective story, but Sayers was the first with deep religious faith. Like many Catholics and Anglo-Catholics of her generation, Sayers was a frequent public apologist for Christianity. Her books also feature some memorable Anglican clergy.

Sayers has, however, been surpassed in importance and popularity by Agatha Christie, whose books remain among the highest number selling in the world. Hardly a reader alive has not read at least one of Christie’s classic mysteries, and though her writing is not without its faults, her plots are magnificent puzzles, the solving of which fills the reader with a genuine sense of accomplishment.

What many readers don’t know is that Christie was a devout Christian, a member of the Church of England who had a deep respect for the Roman Catholic Church. She also had admirers in high places. The famous “Agatha Christie Indult” refers to the permission granted in 1971 by Pope Paul VI for the continued celebration of the Tridentine Latin Mass in England and Wales. When the vernacular replaced Latin in the setting of the Mass, many Roman Catholics in Britain wanted the Latin Mass to remain; in a country so defined by the Church of England, Catholics desired to retain their own liturgical identity. Many artists and intellectuals petitioned the Vatican to preserve the Tridentine Mass in Britain, and the pope agreed.

When Pope Paul VI read the petition, he noted one signature in particular. “Ah, Agatha Christie!” he exclaimed, and he approved the request.

The clergy detectives

Graham Greene, no mean writer of suspense himself in addition to being a Catholic convert, also signed the petition. Yet no Catholic writer is more closely associated with the mystery genre than G.K. Chesterton, whose lovable and brilliant Father Brown appeared in over 50 stories, and who—like so many famous fictional detectives—has been adapted into multiple seasons of memorable television series.

Father Brown was based upon a parish priest instrumental in Chesterton’s conversion, and the character was immensely popular, particularly within British literary circles. Christie adored him; Ellery Queen named him along with Sherlock Holmes as the greatest detective of them all; and Evelyn Waugh even honors Father Brown in the novel “Brideshead Revisited” by describing conversion to Catholicism as being like Father Brown’s declaration, “I caught the thief with an unseen hook and an invisible line which is long enough to let him wander to the ends of the world and still to bring him back with a twitch upon the thread.”

Father Brown’s secret, according to the priest himself, is simple: “I try to get inside a man … thinking his thoughts, wrestling with his passions, till I have bent myself into his posture … and when I am quite sure that I feel like the murderer, of course I know who he is.” That sort of empathy is essential for success as both detective and priest.

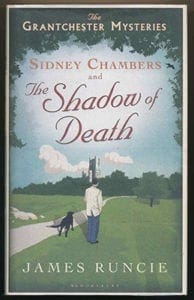

One of the more recent clergy detectives in mystery fiction is James Runcie’s Canon Sidney Chambers, an Anglican parish priest in Cambridge. Canon Chambers’ parish is in Grantchester, a particularly beautiful area of Cambridge, and a place that should be more associated with contemplation than with crime. Yet like Christie’s village of St. Mary Mead, Grantchester becomes a microcosm within which one can observe all of human nature at work.

Runcie knows his material, and well he should, for his late father was once the Archbishop of Canterbury. The Grantchester books—particularly the first, “The Shadow of Death”—are a delight to read, as they hearken back to a golden age of British “cozy” mysteries. And Canon Chambers is a memorable and likable character, endowed with admirable virtues and interesting faults. Most importantly, Runcie never lets the reader forget that his detective is first of all a vicar; the books offer a refreshingly unapologetic portrayal of Christian beliefs and practices, and the television adaptations respect this.

Finally, Canon Chambers is not perfect. He has appetites. He has passions. He has a complicated past. If anyone knows about the difficulty of reconciling abstinence with indulgence, it’s Sidney Chambers.

Runcie reveals to the reader the difficulties associated with a priestly vocation, challenges that most readers often take for granted. While he respects the life of the priest, however, Runcie also pays tribute to the literary past with which Canon Chambers is associated.

The mystery must conclude with a sense of justice. That this sense of justice is often cathartic and even redemptive for the reader makes it a perfect genre for the writer of faith. Yet the best mystery writers know, like St. Thomas Aquinas, that faith is affirmed and supported by reason. The very best detective stories value belief as well as the powers of deduction, and they remain popular, even enduring, for validating the full potential of the human nature they so memorably examine.

David A. King, Ph.D., is associate professor of English and Film Studies at Kennesaw State University and director of adult education at Holy Spirit Church in Atlanta.